CS 3100: Program Design and Implementation II Lecture 2: Inheritance and Polymorphism in Java

©2025 Jonathan Bell, CC-BY-SA

Context from L1:

Students saw Java syntax, primitives vs references, Hello World

This lecture shows how Java's type system enables good design

Key theme: Inheritance isn't just code reuse—it's modeling real-world relationships

→ Transition: Here's what you'll be able to do after today...

Learning Objectives

After this lecture, you will be able to:

Describe why inheritance is a core concept of OOP Define a type hierarchy and understand superclass/subclass relationships Explain the role of interfaces and abstract classes Describe the JVM's implementation of dynamic dispatch Describe the difference between static and instance methods Describe the JVM exception handling mechanism Recognize common Java exceptions and when to use them Time allocation:

Objectives 1-3: Inheritance, interfaces, abstract classes (~25 min)

Objective 4: Dynamic dispatch—crucial for understanding polymorphism (~10 min)

Objective 5: Static vs instance—quick distinction (~5 min)

Objectives 6-7: Exceptions—error handling patterns (~10 min)

Why this matters: Students will build a class hierarchy in A1 (Quantity, Ingredient classes). They need to understand when to use interfaces vs abstract classes, and how to throw appropriate exceptions.

→ Transition: Let's start with the fundamental question: why do we use inheritance at all?

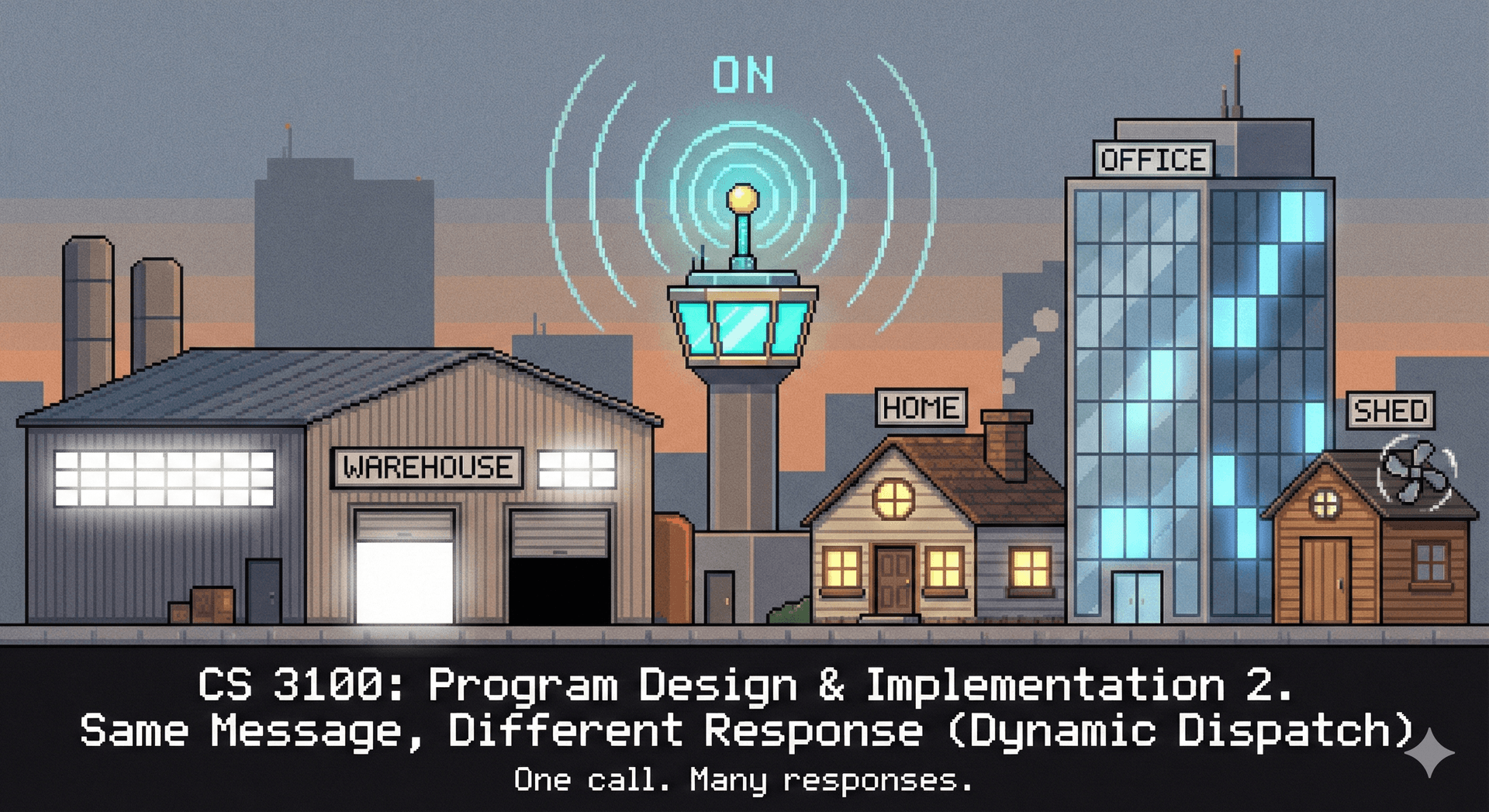

Software Models Real-World Domains Core principle: Make your data mean something

The domain:

Banking apps model accounts, transactions, customers

Games model players, items, enemies

IoT apps model devices, rooms, schedules

Why this matters:

Domain vocabulary → better names

Domain relationships → clearer structure

Domain understanding → code that stakeholders can discuss

Image shows: Left side has meaningless column names (uid_1, type_cd); right side has meaningful types (sender: Account, recipient: Account). The meaningful model answers auditor questions directly.

→ Transition: Let's explore a concrete domain—smart home IoT devices...

Example Domain: Smart Home IoT

Let's design a system to control smart home devices

What concepts exist in this domain?

Devices (lights, fans, thermostats, sensors...) Rooms, zones Schedules, automations Users, permissions

Today we'll focus on devices

Why IoT example:

Relatable—many students have smart lights/thermostats

Clear hierarchies—different device types with shared behaviors

We'll reuse this example in future lectures

Brainstorm briefly: Ask students what devices they have. This grounds the abstraction in their experience.

A1 connection: Recipe domain has similar structure—Quantity types, Ingredient types, etc.

→ Transition: These device concepts naturally form hierarchies—let's see how...

In the real world, concepts have natural relationships:

A dimmable light is a kind of light A light is a kind of device A fan is a kind of device

These "is-a" relationships form a hierarchy

Key phrase: "is-a" relationship

This is the test for when inheritance is appropriate

If X "is-a" Y, then X should extend/implement Y

If X "has-a" Y, use composition instead (covered later)

Students will use this language when designing A1 classes. E.g., "A VolumeQuantity IS-A Quantity"

→ Transition: How does OOP let us capture these relationships?

Inheritance Captures "Is-A" Relationships

Inheritance is a core OOP concept that lets us model "is-a" relationships

Child types inherit behavior from parent types Child types can extend with new capabilities Child types can override to specialize behavior

Bonus: Avoid duplicating code → easier to maintain

Three verbs of inheritance:

Inherit — get parent's methods/fields automaticallyExtend — add new methods/fieldsOverride — replace parent's method with specialized version Practical payoff: Write turnOn/turnOff once in Light, not in every light subtype

Common misconception: Inheritance is primarily for code reuse. Correct view: it's for modeling IS-A relationships; code reuse is a bonus.

→ Transition: Let's define the base type that all devices share...

Base Types Define Shared Capabilities

Every device in our system shares some basic capabilities:

identify() — help a human find the device (e.g., flash a light, wiggle a shade or fan)isAvailable() — check if the device is reachableWhy interface here:

We're defining a contract: "all devices must do these things"

No implementation yet—different devices identify themselves differently

Interface = "what," not "how"

identify() example: Lights flash, fans wiggle, speakers beep. Same concept, different implementations. This foreshadows polymorphism.

→ Transition: Now let's add a skeletal implementation that provides common behavior...

Subtypes Add Specialized Behavior

A skeletal implementation provides shared behavior; subclasses specialize:

Pattern: Interface → Skeletal Abstract Class → Concrete Classes

IoTDevice: pure contract (interface)

BaseIoTDevice: implements isAvailable(), leaves identify() abstract

Light/Fan: add device-specific behavior

This pattern appears in Java stdlib:

List → AbstractList → ArrayList

Map → AbstractMap → HashMap

A1 parallel: Students might have Quantity interface → AbstractQuantity → VolumeQuantity/MassQuantity

→ Transition: But why separate Light and Fan? Couldn't we generalize?

Discussion: Why Separate Types?

Lights and fans both have on/off behavior...

Why not just use one SwitchableDevice type?

Think about: What does the domain tell us? How would users think about these?

Discussion prompt (~2 min)

Expected answers:

Lights have brightness, color temp, RGB

Fans have speed, direction (reversible)

Constraints differ (dimming 0-100% vs speed 1-3-5)

Users think of them as different things

Key insight: The domain tells us they're fundamentally different. Over-generalizing loses information and makes code harder to understand.

Counter-example: If we later find lights and fans really do share switchable behavior, we can extract a Switchable interface. Start specific, generalize when needed.

→ Transition: Light itself has subtypes—not all lights are equal...

Hierarchies Can Go Multiple Levels Deep

Not all lights are the same — some have more features:

Hierarchy depth:

SwitchedLight: simplest—just on/off

DimmableLight: adds brightness control

TunableWhiteLight: extends DimmableLight (not Light!)—IS-A DimmableLight with color temp

Design decision: TunableWhiteLight extends DimmableLight because all tunable white lights are also dimmable. This reflects real products.

Note: Each subtype overrides identify() because each identifies itself differently (flash pattern varies by capability).

→ Transition: Let's see the complete picture...

The Complete Hierarchy Pause here: Let students trace the relationships

What does TunableWhiteLight inherit?

Where is identify() implemented?

Which classes are abstract vs concrete?

A1 connection: Students will build a similar hierarchy for recipes. Encourage them to sketch it out before coding.

→ Transition: Let's trace exactly what each type gets from inheritance...

Each Level Inherits Everything Above It Type Inherits From Adds IoTDevice— identify(), isAvailable()BaseIoTDeviceIoTDeviceImplements isAvailable(), adds deviceId LightBaseIoTDeviceturnOn(), turnOff(), isOn()DimmableLightLightsetBrightness(), getBrightness()TunableWhiteLightDimmableLightsetColorTemperature(), getColorTemperature()

Each level inherits everything from above and adds new capabilities

Key observation: TunableWhiteLight gets 8+ methods but only declares 2

identify(), isAvailable() from IoTDevice

deviceId, isAvailable() impl from BaseIoTDevice

turnOn(), turnOff(), isOn() from Light

setBrightness(), getBrightness() from DimmableLight

Plus its own: setColorTemperature(), getColorTemperature()

This is the power of inheritance: Capability accumulates through the hierarchy with minimal code duplication.

→ Transition: Let's summarize the principles before diving into Java syntax...

Your Code Should Tell a Story About the Domain Understand the domain before writing code"Is-a" relationships in the domain → inheritance in codeCommon behavior goes in parent typesSpecialized behavior goes in child typesGood names come from domain vocabulary Summary of design principles:

Talk to stakeholders, understand the domain FIRST

Look for "is-a" relationships—they suggest inheritance

Common behavior bubbles up; specialized behavior pushes down

Use domain vocabulary: DimmableLight, not LightWithBrightnessControl

A1 relevance: Recipe domain has clear vocabulary: Ingredient, Quantity, Recipe. Use those names.

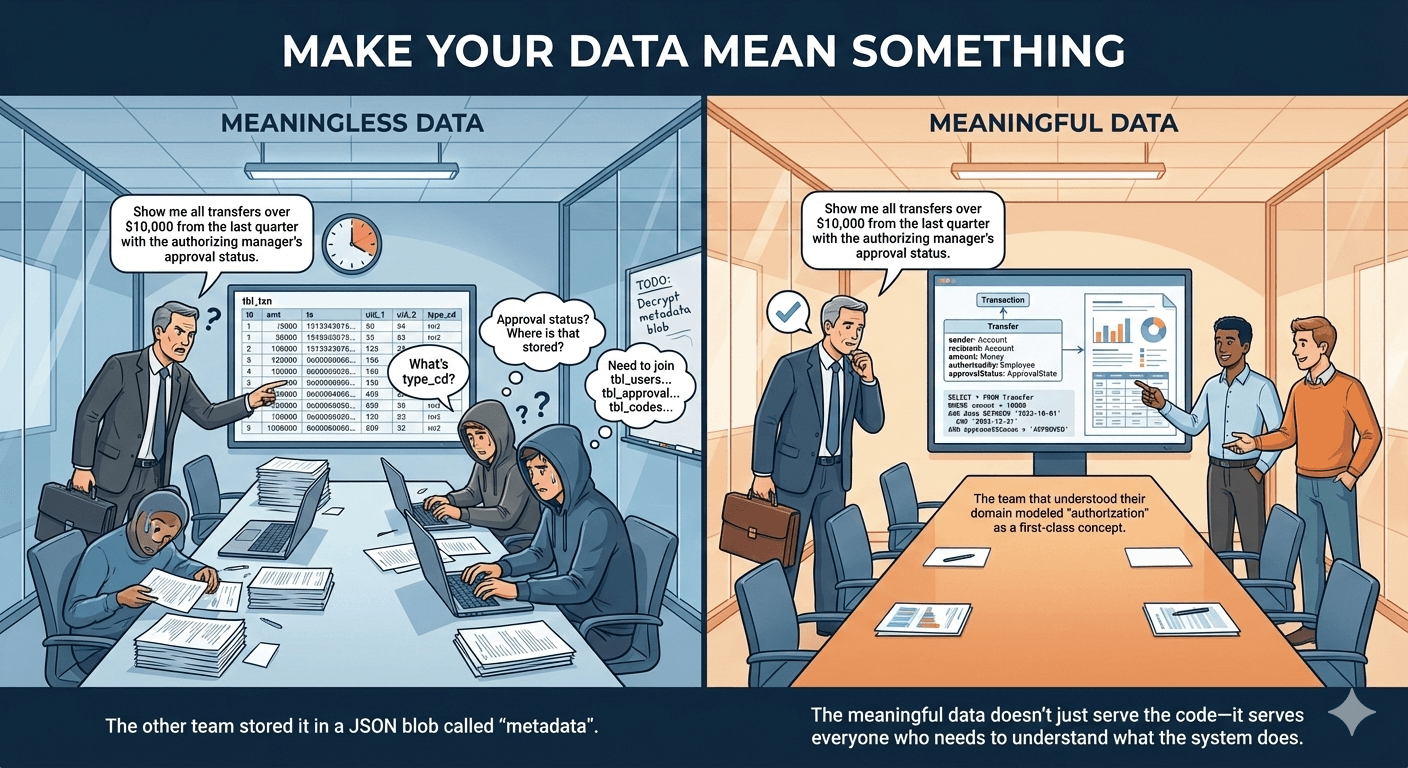

→ Transition: Before coding, it helps to sketch your types...

Sketch Your Types Before You Code Why sketch first:

Discovers concepts you hadn't considered

Finds gaps in understanding

Communicates with teammates/stakeholders

Catches design issues before implementation

Doesn't need to be formal UML —boxes and arrows on paper work fine. This is part of "shift left" from L1.

We cover domain modeling formally later (around L12), but students should start sketching now for A1.

→ Transition: Now let's see how Java specifically represents these hierarchies...

Java Uses Classes and Interfaces for Hierarchies

Every language represents type hierarchies differently

Java uses two constructs:

Classes

Concrete implementations

Interfaces

Behavioral contracts

Language comparison:

Python: classes with multiple inheritance

Go: interfaces only (no classes)

Java: single class inheritance + multiple interfaces

Key Java constraint: You can only extend ONE class, but implement MANY interfaces. This is deliberate—avoids the "diamond problem" (coming up).

→ Transition: Let's look at what classes can do...

Classes Extend One Superclass, Implement Many Interfaces Can extend exactly one superclass Can implement multiple interfaces Inherit fields and methods from superclass Can override inherited methods Can be concrete or abstract Defining a Class public class TunableWhiteLight extends DimmableLight { private int startupColorTemperature ; public TunableWhiteLight ( String deviceId , int colorTemp , int brightness ) { super ( deviceId , brightness ) ; this . startupColorTemperature = colorTemp ; } @Override public void turnOn ( ) { setColorTemperature ( startupColorTemperature ) ; super . turnOn ( ) ; } public void setColorTemperature ( int colorTemperature ) { } public int getColorTemperature ( ) { } } Key syntax elements:

extends DimmableLight — names the superclasssuper(...) — calls parent constructor, MUST be first line@Override — annotation that catches typos at compile timesuper.turnOn() — calls parent's version (extend behavior, don't replace)this.startupColorTemperature — disambiguates field from parameter Pattern in turnOn(): Do subclass-specific work, then delegate to parent. Very common.

→ Transition: Let's review the key syntax points...

Key Syntax Points extendsSpecifies the superclass super(...)Call the parent's constructor (must be first line) @OverrideAnnotation indicating method override super.method()Call the parent's version of a method this.fieldRefers to instance field (not parameter)

Visibility Controls Who Can Access Your Code Modifier Accessible By publicAny class protectedSame class, subclasses, same package privateSame class only (none) Package-private — avoid!

Always specify visibility explicitly

When to use each:

public — API methods that others should callprotected — fields/methods that subclasses needprivate — internal implementation details Package-private (no modifier): Confusing default, rarely intentional. Always be explicit.

A1 note: Students should use private fields with public getters (encapsulation).

→ Transition: Before we go further, let's discuss a crucial principle about inheritance...

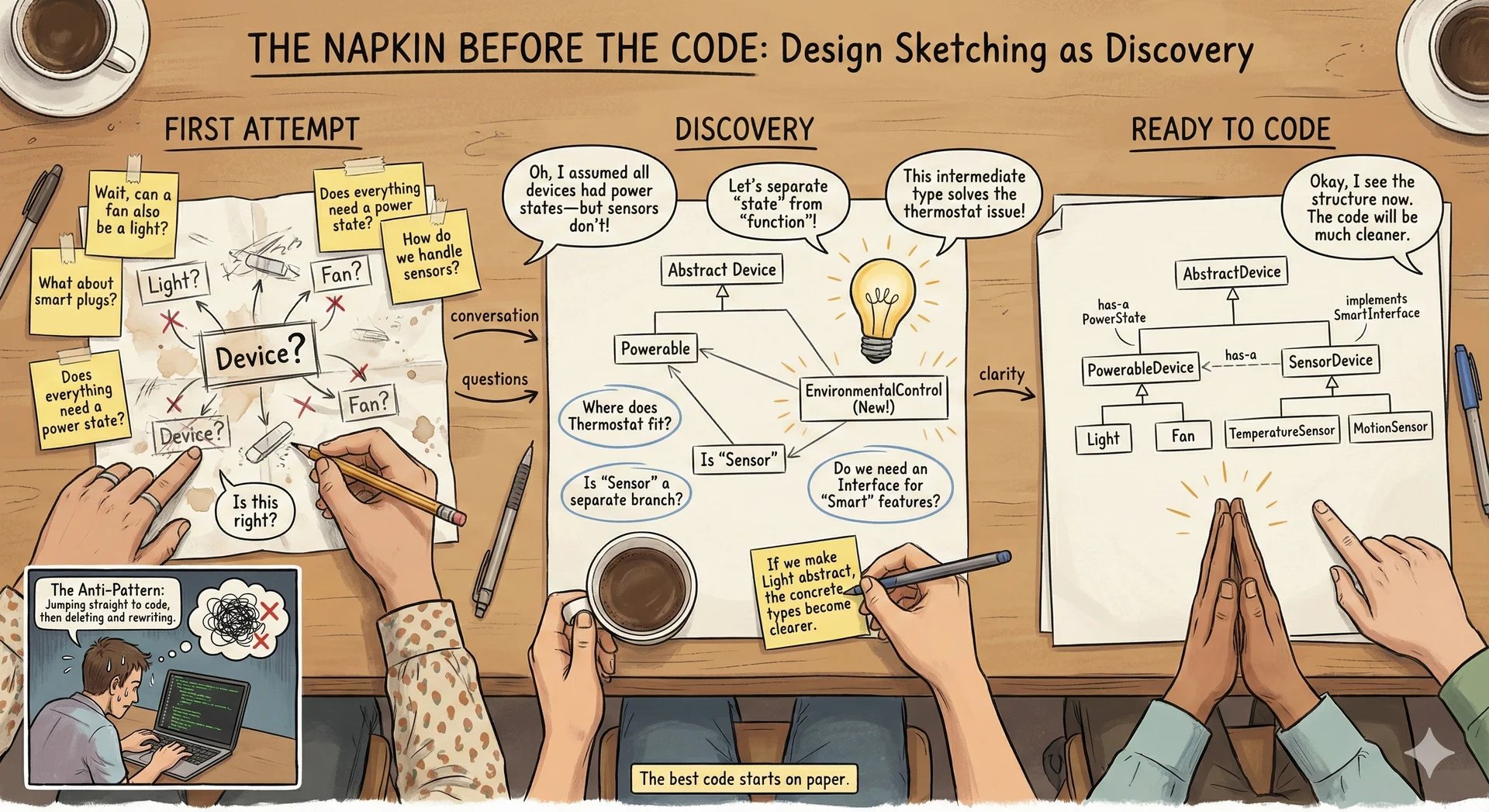

The Liskov Substitution Principle "If S is a subtype of T, then objects of type T may be replaced with objects of type S without altering the correctness of the program."

— Barbara Liskov, 1987

In plain terms: If your code works with a Light, it must work with ANY Light subtype—DimmableLight, TunableWhiteLight, future types you haven't written yet.

Classic violation: Square extends Rectangle. If setWidth() on Rectangle doesn't affect height, but on Square it must change height to match... that breaks code expecting Rectangle behavior.

Key insight: Inheritance is a CONTRACT. Subtypes must honor the supertype's behavioral promises.

→ Transition: Let's visualize what this means...

Subtypes Must Behave Like Their Supertypes Image metaphor: Socket = supertype contract, pins = method signatures

DimmableLight plugs in, turnOn() lights up ✓

TunableWhiteLight plugs in (extra pins tucked away), lights up ✓

BrokenLight's pins fit BUT produces smoke instead of light ✗

Key insight: Matching signatures (pins fit) isn't enough. Behavior must also match. The compiler checks signatures; YOU must ensure behavioral correctness.

→ Transition: Let's see substitution in action with code...

Subclasses Work Wherever Supertypes Are Expected Light [ ] lights = new Light [ 2 ] ; TunableWhiteLight light1 = new TunableWhiteLight ( "light-1" , 2700 , 100 ) ; lights [ 0 ] = light1 ; DimmableLight light2 = new DimmableLight ( "light-2" , 100 ) ; lights [ 1 ] = light2 ; for ( Light l : lights ) { l . turnOn ( ) ; }

A subclass can always be used where a superclass is expected

This is polymorphism in action:

Array holds Light references

Actual objects are TunableWhiteLight and DimmableLight

Loop calls turnOn() without knowing specific types

JVM figures out which turnOn() to call (next section!)

Benefit: Code written for Light works with ANY Light subtype—even ones written after your code.

→ Transition: But what if we need subclass-specific features?

Downcasting Accesses Subclass-Specific Features

To access subclass-specific methods, cast the reference:

TunableWhiteLight twl = ( TunableWhiteLight ) lights [ 0 ] ; twl . setColorTemperature ( 2200 ) ; ( ( TunableWhiteLight ) lights [ 0 ] ) . setColorTemperature ( 2200 ) ;

⚠️ Throws ClassCastException if the cast is invalid!

When you need to downcast:

You have a supertype reference but know it's actually a subtype

You need subclass-specific methods

Danger: If you're wrong, ClassCastException at runtime

Code smell: Frequent downcasting suggests your design needs work. If you're constantly checking types and casting, consider redesigning.

→ Transition: Now let's look at interfaces and abstract classes in detail...

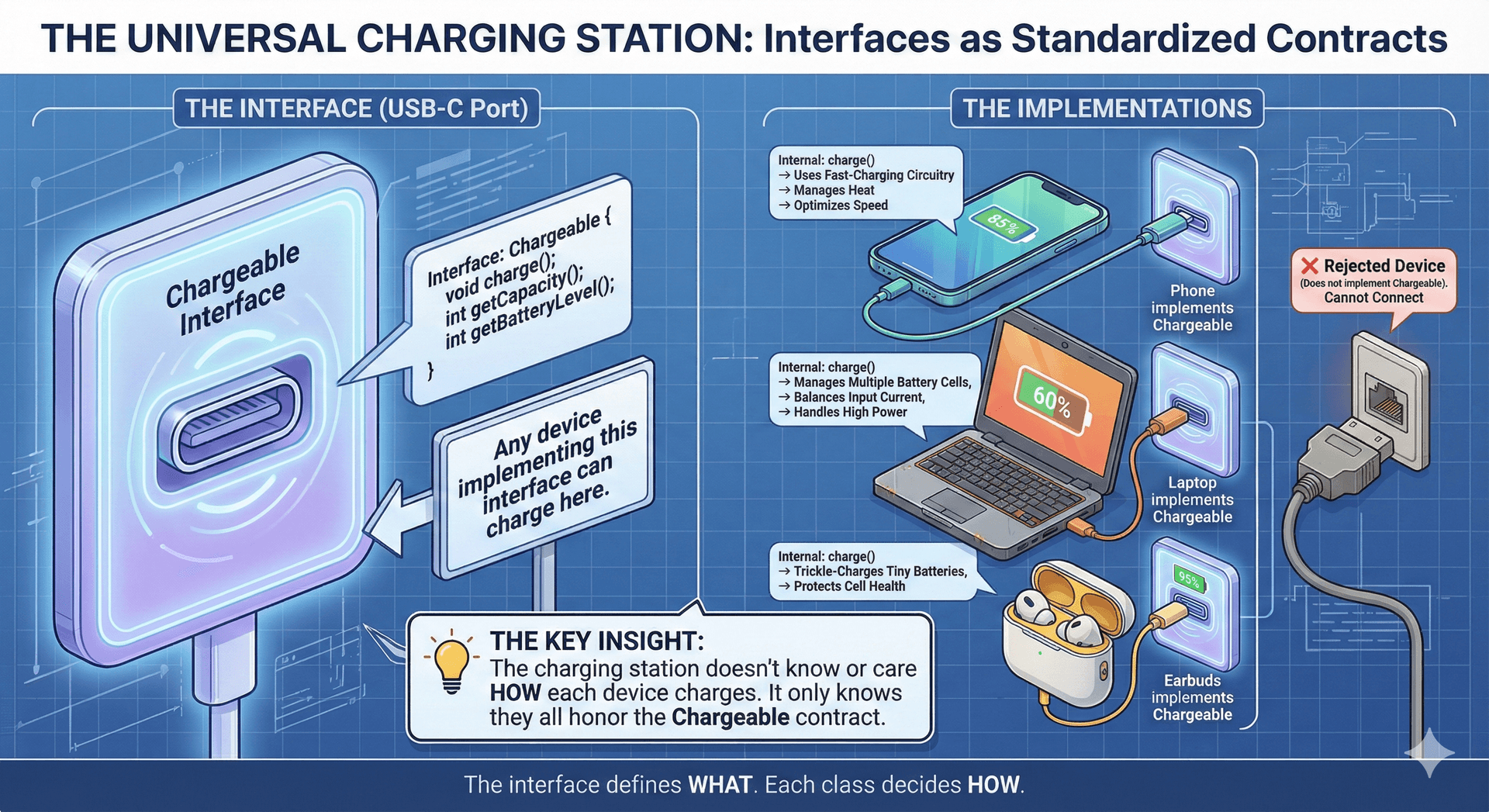

Interfaces Define Contracts Without Implementation

Define a contract — methods a class must implement A class can implement multiple interfaces Cannot be instantiated directly No instance fields (only constants) Key characteristics:

Pure contract: specifies WHAT, not HOW

Multiple inheritance safe: no implementation to conflict

Can't have instance state (fields)

When to use: When you want to define capabilities that unrelated classes might share. E.g., Comparable, Serializable.

→ Transition: Let's see the syntax...

Defining an Interface public interface IoTDevice { void identify ( ) ; boolean isAvailable ( ) ; }

Note: public is optional in interface methods (always public)

Syntax notes:

Methods are implicitly public—can omit the keyword

No method bodies (in basic interfaces)

Javadoc comments = the behavioral contract

The contract: Anyone implementing IoTDevice promises to provide identify() and isAvailable() that behave as documented.

→ Transition: What if we want shared implementation too?

Abstract Classes Provide Skeletal Implementations

A skeletal implementation provides shared behavior while leaving specifics abstract:

public abstract class BaseIoTDevice implements IoTDevice { protected String deviceId ; protected boolean isConnected ; public BaseIoTDevice ( String deviceId ) { this . deviceId = deviceId ; } @Override public boolean isAvailable ( ) { return this . isConnected ; } public abstract void identify ( ) ; } Abstract class features:

Can have fields (often protected for subclass access)

Can implement some methods (isAvailable here)

Can leave others abstract (identify)

Has constructor (called via super())

Why use: When related classes share state or implementation, not just contract.

→ Transition: How do you choose between them?

Use Interfaces for Contracts, Abstract Classes for Shared State Interface Abstract Class Multiple inheritance Yes No Instance fields No Yes Concrete methods Default only Yes Constructor No Yes

Rule of thumb: prefer interfaces; use abstract classes when you need shared state or implementation

Decision guide:

Start with interface (maximum flexibility)

If you find shared state/implementation, add abstract class

Pattern: Interface + Skeletal Abstract Class (like Java's List/AbstractList)

A1 guidance: Students might have Quantity interface with AbstractQuantity providing shared validation.

→ Transition: Now let's understand how the JVM actually calls methods...

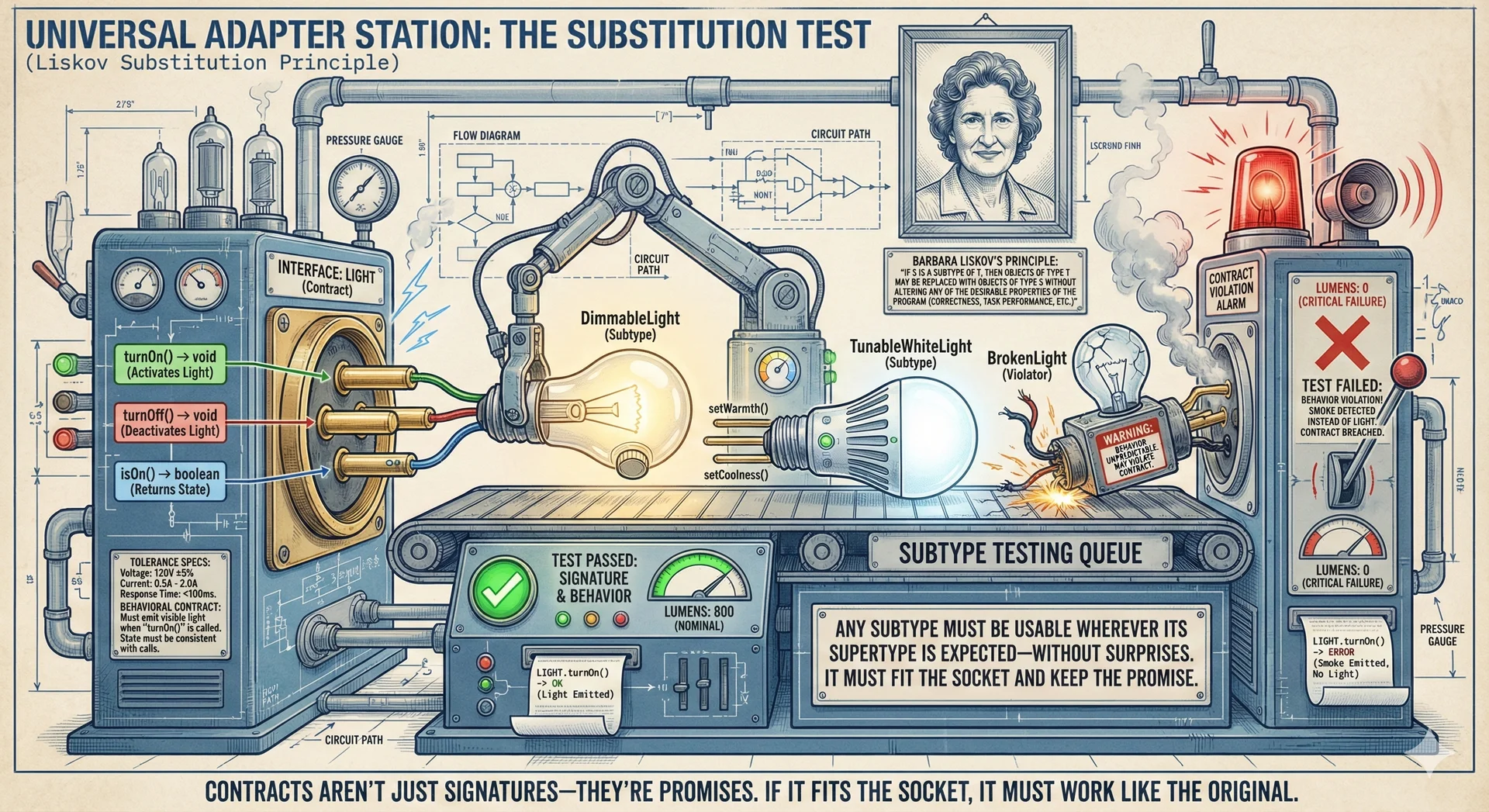

The JVM Chooses Methods at Runtime, Not Compile Time

How does the JVM know which method to call?

Light [ ] lights = new Light [ ] { new TunableWhiteLight ( "light-1" , 2700 , 100 ) , new DimmableLight ( "light-2" , 100 ) } ; for ( Light l : lights ) { l . turnOn ( ) ; } The question: Variable type is Light. Object types are TunableWhiteLight and DimmableLight. Which turnOn() runs?

Answer preview: The ACTUAL object's turnOn(), not the variable type's.

This is dynamic dispatch —method selection happens at runtime based on the object's actual type.

→ Transition: Let's trace through the algorithm...

Method Lookup Walks Up the Type Hierarchy

To call method m on object o of runtime type T :

If T declares m , use that Otherwise, check T 's superclass recursively If still not found, use default interface method (if any) Runtime type matters, not compile-time type!

The algorithm:

Look at runtime type (what the object actually IS)

Does that class declare the method? If yes, use it.

If not, check superclass. Repeat.

Default interface methods are last resort (rare).

Key insight: The variable's declared type determines what methods you CAN call. The object's runtime type determines which implementation RUNS.

→ Transition: Let's trace through specific examples...

Which Method Gets Called? Call: twl.turnOn()

TunableWhiteLight twl = new TunableWhiteLight ( "living-room" , 2700 , 100 ) ; twl . turnOn ( ) ; Runtime type: TunableWhiteLight

Step 1: Does TunableWhiteLight declare turnOn()?

✓ Yes! Use TunableWhiteLight.turnOn()

Example 1: Simple case

Variable type: TunableWhiteLight

Runtime type: TunableWhiteLight

Step 1: TunableWhiteLight declares turnOn()? YES → use it

Diagram highlights TunableWhiteLight where method is found.

→ Transition: What about an inherited method?

Which Method Gets Called? Call: twl.setBrightness(50)

TunableWhiteLight twl = new TunableWhiteLight ( "living-room" , 2700 , 100 ) ; twl . setBrightness ( 50 ) ; Runtime type: TunableWhiteLight

Step 1: Does TunableWhiteLight declare setBrightness()? No

Step 2: Check superclass DimmableLight...

✓ Found! Use DimmableLight.setBrightness()

Example 2: Inherited method

TunableWhiteLight doesn't declare setBrightness()

Walk up to DimmableLight—found!

Use DimmableLight.setBrightness()

Diagram shows walking up the hierarchy.

→ Transition: Now the crucial case—what if variable type differs from runtime type?

Which Method Gets Called? Call: light.turnOn()

Light light = new TunableWhiteLight ( "living-room" , 2700 , 100 ) ; light . turnOn ( ) ; Compile-time type: Light

Runtime type: TunableWhiteLight

Step 1: Does TunableWhiteLight declare turnOn()?

✓ Yes! Use TunableWhiteLight.turnOn()

The variable type (Light) doesn't matter — runtime type does!

Example 3: THE KEY CASE

Variable declared as Light

Object is actually TunableWhiteLight

Dispatch uses RUNTIME type: TunableWhiteLight.turnOn()

This is why polymorphism works: Code written for Light automatically gets the right subclass behavior.

→ Transition: One more misconception to address—does casting change this?

Casting Doesn't Change Which Method Runs Light l = new TunableWhiteLight ( "living-room" , 2700 , 100 ) ; l . turnOn ( ) ; ( ( DimmableLight ) l ) . turnOn ( ) ;

The cast doesn't change which method is called

The actual object type at runtime determines the method

Common misconception: Students think casting changes which method runs. It doesn't!

What casting does:

Changes compile-time type (what methods you can CALL)

Does NOT change runtime type (which implementation RUNS)

The object is still a TunableWhiteLight. Casting to DimmableLight just lets you call DimmableLight methods without compiler complaint.

→ Transition: Let's contrast with static methods, which behave differently...

Instance Methods Dispatch Dynamically; Static Methods Don't Instance Methods

Belong to an object Can access this Dynamically dispatchedStatic Methods

Belong to the class No this reference Statically boundKey distinction:

Instance methods: runtime type determines which implementation

Static methods: compiler knows exactly which method at compile time

No dynamic dispatch for static methods. The class name determines the method—no objects involved.

→ Transition: Let's see a static method example...

Static Methods Belong to Classes, Not Objects public class TunableWhiteLight extends DimmableLight { public static int degreesKelvinToMired ( int degreesKelvin ) { return 1000000 / degreesKelvin ; } } int mireds = TunableWhiteLight . degreesKelvinToMired ( 2700 ) ;

No object needed — method is resolved at compile time

When to use static:

Utility methods that don't depend on object state

Factory methods

Pure functions (input → output, no side effects)

Call syntax: Use class name, not an instance. Compiler resolves at compile time.

→ Transition: Now let's switch gears to multiple inheritance...

Some Objects Belong to Multiple Categories

When a class inherits from more than one parent type

Some languages (C++, Python) support this directly for classes

Java allows multiple inheritance only through interfaces

The desire: Real-world objects often belong to multiple categories simultaneously.

Language approaches:

C++: Full multiple class inheritance (complex rules)

Python: Multiple inheritance with MRO (method resolution order)

Java: Single class inheritance, multiple interfaces

Why Java's restriction? Avoids the "diamond problem"—coming up.

→ Transition: Let's see why multiple inheritance is desirable...

Real Objects Often Have Multiple "Is-A" Relationships

Back to our IoT domain... what about a ceiling fan with a light ?

It's both a light AND a fan!

Real product: Hampton Bay ceiling fan with integrated light kit. It genuinely IS both a light and a fan.

Requirements:

Should work anywhere a Light is expected

Should work anywhere a Fan is expected

Single device with unified control

With interfaces: This works! Implement both. But what if Light and Fan were classes?

→ Transition: More examples of this pattern...

More Examples of Multiple Inheritance

Real-world objects often have multiple "is-a" relationships:

A smart thermostat is both a temperature sensor and a controllable device A smartphone is a phone , a camera , and a computer A teaching assistant is both a student and an employee An amphibious vehicle is both a boat and a car

In each case, the object legitimately belongs to multiple categories

Relatable example: Teaching assistant

Pays tuition (student)

Receives paycheck (employee)

Both relationships are real and relevant

These aren't edge cases —multiple categorization is normal in the real world. Languages need ways to model this.

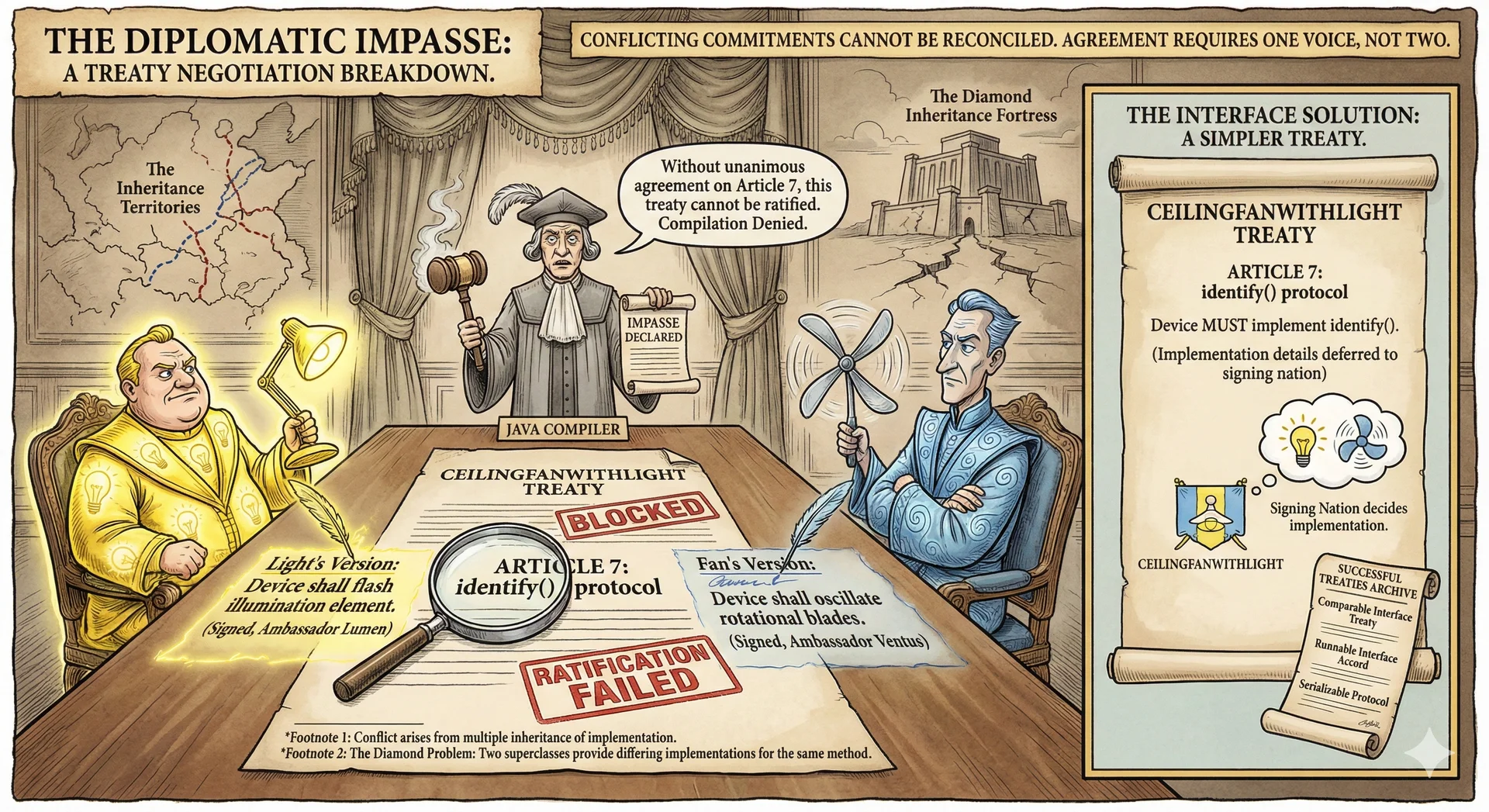

→ Transition: So why doesn't Java allow multiple class inheritance?

Multiple Class Inheritance Creates Ambiguity

Why don't most languages allow multiple class inheritance?

Which identify() does CeilingFanWithLight inherit?

The problem:

Light.identify() → flashes the light

Fan.identify() → wiggles the blades

CeilingFanWithLight extends both... which identify() does it get?

No good automatic answer. The compiler can't decide. This is the "diamond problem."

→ Transition: Let's visualize why this is called the diamond problem...

The Compiler Can't Choose Between Conflicting Implementations Called the "diamond problem" because the inheritance diagram forms a diamond shape. Java avoids this by disallowing multiple class inheritance—you can only extend one class, but implement many interfaces.

Java Avoids the Diamond Problem with Interfaces

Java avoids the diamond problem by restricting multiple inheritance to interfaces:

Interfaces don't provide implementations (usually) No ambiguity about which implementation to inherit The implementing class must provide the implementation public class CeilingFanWithLight implements Light , Fan { @Override public void identify ( ) { flashLight ( ) ; spinBlades ( ) ; } } Java's solution:

Interfaces have no implementation to conflict

YOU must provide identify()—no ambiguity

You decide what it means for this hybrid device

Flexibility: Flash then spin? Spin then flash? Just flash? Your choice.

→ Transition: There's another approach—composition...

Composition: "Has-A" Instead of "Is-A"

Instead of being both types, contain instances of them

Composition approach:

CeilingFanWithLight HAS-A Light and HAS-A Fan

Delegates to them as needed

No inheritance ambiguity—explicit delegation

The diamond notation (o--) represents "has-a" relationship.

→ Transition: Let's see the implementation...

Composition Lets You Control How Behaviors Combine

With composition, we decide how to combine behaviors:

public class CeilingFanWithLight implements IoTDevice { private Light light ; private Fan fan ; @Override public void identify ( ) { light . identify ( ) ; fan . identify ( ) ; } public void turnOnLight ( ) { light . turnOn ( ) ; } public void setFanSpeed ( int speed ) { fan . setSpeed ( speed ) ; } }

✓ Diamond problem solved — we control the delegation

Benefits:

Explicit control over behavior combination

Can swap light/fan implementations at runtime

Easier to test (mock the components)

Tradeoff: CeilingFanWithLight can't substitute for Light or Fan in existing code (no IS-A relationship).

→ Transition: Let's compare the tradeoffs...

Composition Trades Substitutability for Flexibility Advantages

No diamond problem Can swap implementations at runtime More flexible coupling Easier to test (mock components) Disadvantages

Can't substitute for Light or Fan Must manually delegate methods More boilerplate code

"Prefer composition over inheritance" — but know when inheritance fits better

"Prefer composition over inheritance" is a common design principle—but not absolute.

Use inheritance when:

True IS-A relationship

Need substitutability (LSP)

Behavior is core identity

Use composition when:

HAS-A relationship

Want to swap implementations

Combining unrelated capabilities

→ Transition: You can actually combine both approaches...

Combine Interfaces and Composition for Maximum Flexibility

Best of both worlds: composition with interface implementation

public class CeilingFanWithLight implements Light , Fan , IoTDevice { private Light lightComponent ; private Fan fanComponent ; @Override public void identify ( ) { lightComponent . identify ( ) ; fanComponent . identify ( ) ; } @Override public void turnOn ( ) { lightComponent . turnOn ( ) ; } @Override public void setSpeed ( int speed ) { fanComponent . setSpeed ( speed ) ; } }

✓ Can substitute for Light, Fan, and IoTDevice!

Best of both worlds:

Implements interfaces → substitutable for Light, Fan, IoTDevice

Contains components → explicit delegation, swappable implementations

More boilerplate, but maximum flexibility

This pattern is common in real codebases. Worth knowing.

→ Transition: Now let's cover exception handling...

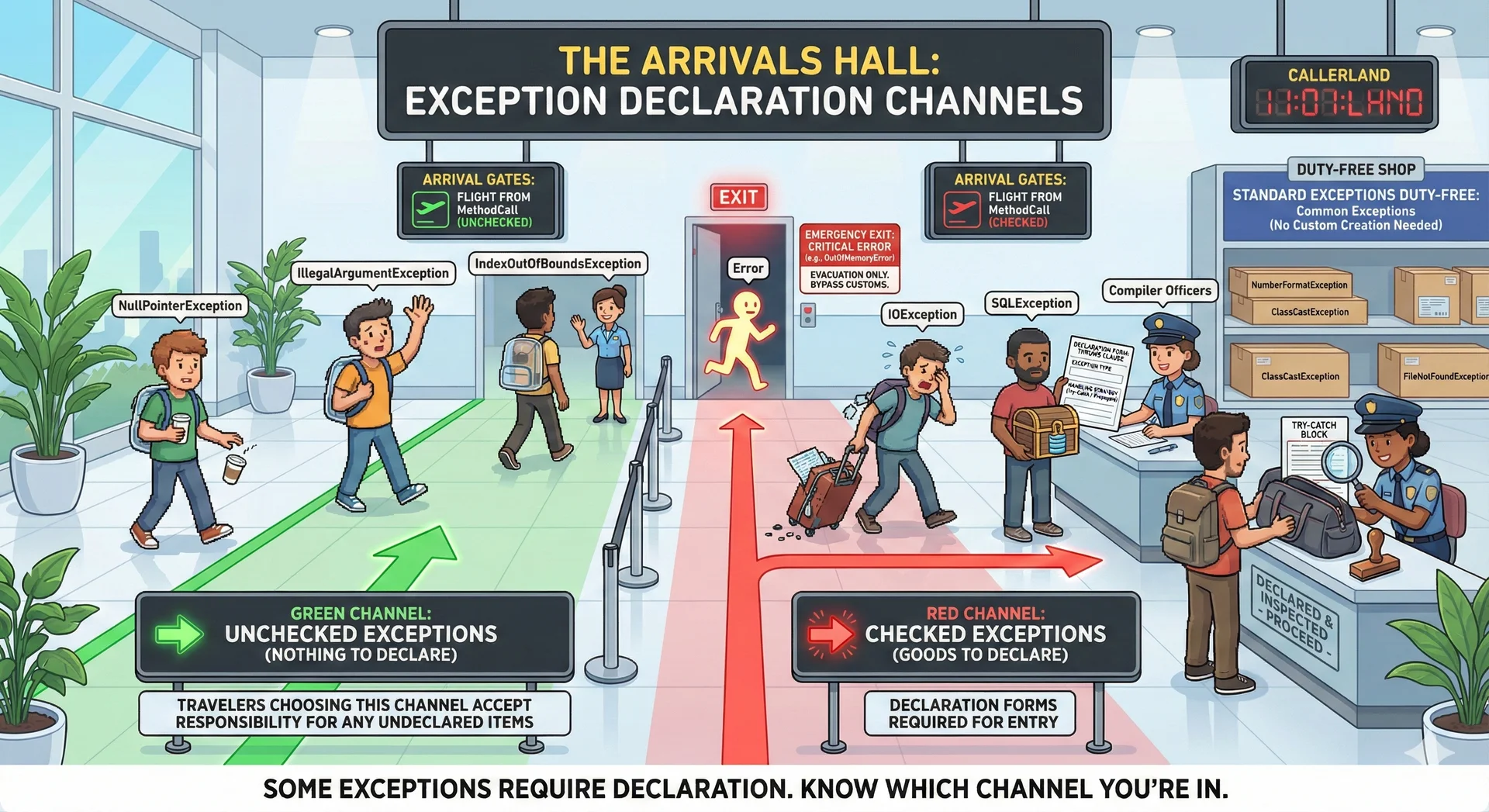

Java's Exception Hierarchy Distinguishes Error Types

All exceptions extend Throwable

Exception hierarchy uses inheritance!

Three branches:

Error: Fatal JVM problems (OutOfMemoryError, StackOverflowError). Don't catch these.Exception (checked): Recoverable problems that must be declared/caughtRuntimeException (unchecked): Programming errors, no declaration required Python comparison: All exceptions are unchecked. Java forces explicit handling of expected failures.

→ Transition: Let's understand checked vs unchecked...

Checked Exceptions Must be Declared public void turnOn ( ) throws IOException { } Airport customs metaphor:

Green channel (unchecked): RuntimeException—walk through, no paperworkRed channel (checked): IOException, SQLException—must declare with throws or catch The compiler is the customs officer —enforces that you handle checked exceptions.

→ Transition: Let's clarify Error vs Exception...

Errors Are Fatal; Exceptions Are Recoverable ErrorExceptionTypically fatal Recoverable JVM-detected problems Application-level problems OutOfMemoryErrorIOExceptionStackOverflowErrorNullPointerException

Don't throw Error in your code!

Error: JVM-level problems you can't recover from. Out of memory? Program is doomed. Don't throw Errors in application code.

Exception: Things your code can potentially handle. File not found? Try a different file. Network timeout? Retry.

→ Transition: Within Exception, there's another distinction...

Checked Exceptions Force Callers to Handle Failure Checked Unchecked Must be caught or declared No requirement to handle Subclass of Exception Subclass of RuntimeException IOExceptionNullPointerExceptionSQLExceptionIllegalArgumentException

Python: all exceptions are unchecked

Checked (compile-time enforcement):

IOException, SQLException—expected failures from external systems

Must declare with throws or handle with try-catch

Unchecked (no enforcement):

NullPointerException, IllegalArgumentException—programming errors

Can happen anywhere; requiring declaration would be impractical

A1 relevance: Students will throw IllegalArgumentException for invalid inputs.

→ Transition: Which exceptions should you use?

Prefer Standard Exceptions Over Custom Ones IllegalArgumentExceptionInvalid method argument NullPointerExceptionUnexpected null value IllegalStateExceptionObject in wrong state for operation IndexOutOfBoundsExceptionIndex outside valid range UnsupportedOperationExceptionOperation not supported

Prefer standard exceptions over custom ones!

Use standard exceptions:

IllegalArgumentException: Bad input (negative quantity, null where not allowed)NullPointerException: Null passed where unexpectedIllegalStateException: Wrong order of operations (calling next() on empty iterator)IndexOutOfBoundsException: Array/list index problemsUnsupportedOperationException: Method not implemented Custom exceptions: Only for domain-specific errors that don't fit these.

→ Transition: How do you use these effectively?

Fail Fast: Check Parameters and Throw Clear Exceptions public void setColorTemperature ( int colorTemperature ) { if ( colorTemperature < 1000 || colorTemperature > 10000 ) { throw new IllegalArgumentException ( "Color temperature must be between 1,000 and 10,000 Kelvin" ) ; } }

Check parameters early — fail fast with clear messages

"Fail fast" principle:

Check parameters at method entry

Throw immediately with clear message

Don't let bad values propagate and cause confusing errors later

Good error message includes:

What was wrong

What was expected

Document in Javadoc

A1 requirement: Students must validate inputs and throw appropriate exceptions.

→ Transition: One important anti-pattern to avoid...

⚠️ Exceptions Are for Exceptional Cases try { int i = 0 ; while ( true ) { lights [ i ] . turnOn ( ) ; i ++ ; } } catch ( ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException e ) { } for ( int i = 0 ; i < lights . length ; i ++ ) { lights [ i ] . turnOn ( ) ; } Anti-pattern: Using exceptions for flow control

Slow (exceptions have overhead)

Hard to read

Confusing—exceptions should mean something went wrong

Rule: Exceptions for exceptional situations only. Not for "did I reach the end of the array?"

→ Transition: Let's summarize what we've learned...

Summary Inheritance models "is-a" relationships & enables code reuseInterfaces define contracts; abstract classes share implementationMultiple inheritance : desirable but causes diamond problem; Java uses interfacesLiskov Substitution : subtypes must be substitutable for supertypesDynamic dispatch : runtime type determines which method runsExceptions : checked vs unchecked; favor standard exceptions