CS 3100: Program Design and Implementation II

Lecture 4: Specifications and Common Contracts

©2025 Jonathan Bell, CC-BY-SA

Learning Objectives

After this lecture, you will be able to:

- Describe the role of method specifications in achieving program modularity and improving readability

- Evaluate the efficacy of a given specification using the terminology of restrictiveness, generality, and clarity

- Utilize type annotations to express invariants such as non-nullness

- Define the role of methods common to all Objects in Java (toString, equals, hashCode, compareTo)

Humans Can Only Hold 7±2 Items in Working Memory

Which is easier to remember?

- Random order: 50, 30, 60, 20, 80, 10, 40, 70

- Pattern: 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80

Chunking Lets Us Manage More Than 7 Items

Chunking = organizing information into meaningful units

- "FBI" is 1 chunk, not 3 letters

- "555-1234" is 2 chunks, not 7 digits

- A chess master sees "castled king position" not 5 pieces

Expert programmers chunk code the same way:

- "Binary search" → one chunk (not 15 lines)

- "HashMap lookup" → one chunk (not the internal algorithm)

Specifications Enable Mental Chunking for Code

When reading a program, we want to understand method behavior without reading the implementation.

Without spec: 🤯

public boolean mystery(Object[] arr, Object o) {

for (int i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

if (arr[i].equals(o)) return true;

}

return false;

}

Must read every line to understand

With spec: 😌

/**

* Returns true if this collection contains

* the specified element.

* @return true if this collection contains o

*/

boolean contains(Object o);

Spec tells you what it does

You Spend 10x More Time Reading Code Than Writing It

Consider understanding this call from L3:

Map<String, List<IoTDevice>> devicesByRoom = new HashMap<>();

devicesByRoom.get("living-room").add(new DimmableLight("lr1", 100));

Without spec:

- Open HashMap source (2000+ lines)

- Trace through hash buckets

- Understand resize logic

- Time: 30+ minutes

With spec:

- Read Map.get() Javadoc

- "Returns the value for this key, or null"

- Time: 30 seconds

You used HashMap without reading its 2000-line implementation!

A Good Specification Lets You Predict Behavior

The goal: a developer can understand what a method does without reading its code.

- Any implementation that satisfies the spec is correct

- Any implementation that violates the spec is incorrect

- The spec should be easier to understand than the implementation

But how do we evaluate whether a specification is good?

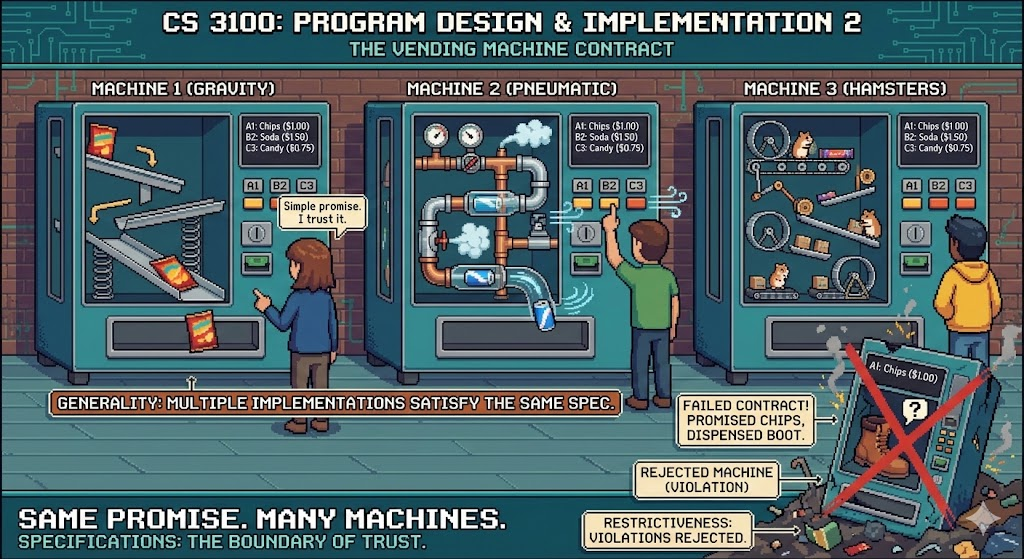

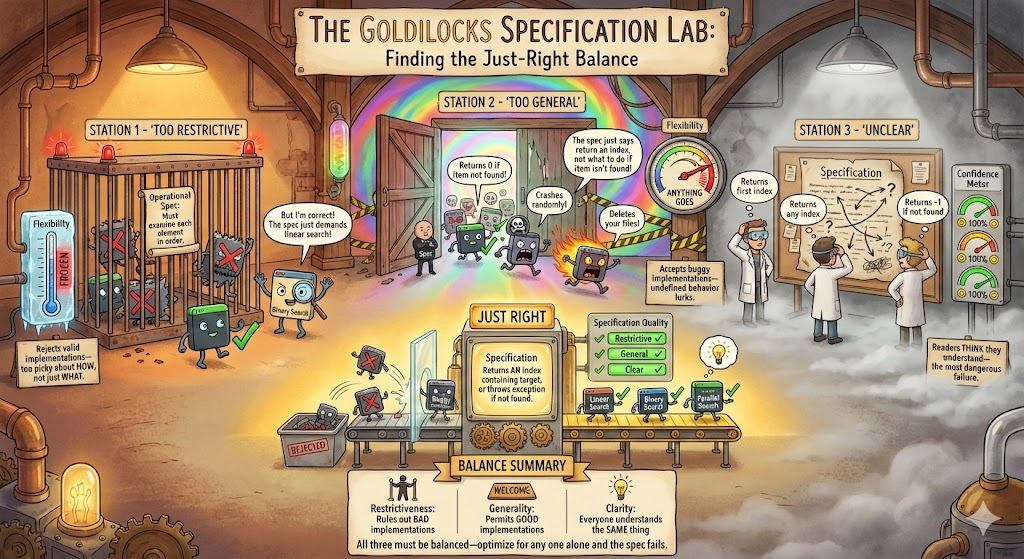

Good Specifications Balance Three Criteria

Restrictive Specs Rule Out Bad Implementations

A spec is restrictive if it rules out implementations that clients would find unacceptable.

Think of it as: "What BAD behaviors does this spec prohibit?"

- Does it specify what happens for ALL inputs?

- Does it prohibit surprising or dangerous behavior?

- Could a malicious implementer satisfy it while being useless?

Under-Specified Behavior Allows Bugs to Hide

Consider this spec for Map.get():

/**

* Returns the value associated with the specified key.

* @param key the key whose value is to be returned

* @return the value associated with key

*/

V get(Object key);

What happens if the key isn't in the map?

- Return null?

- Throw KeyNotFoundException?

- Return a default value?

Every Input Needs Defined Behavior

✓ The actual Map.get() specification:

/**

* Returns the value to which the specified key is mapped,

* or null if this map contains no mapping for the key.

*

* @param key the key whose associated value is to be returned

* @return the value to which the specified key is mapped,

* or null if this map contains no mapping for the key

* @throws ClassCastException if the key is of an inappropriate type

* @throws NullPointerException if the key is null and this map

* does not permit null keys

*/

V get(Object key);

Now every input has defined behavior.

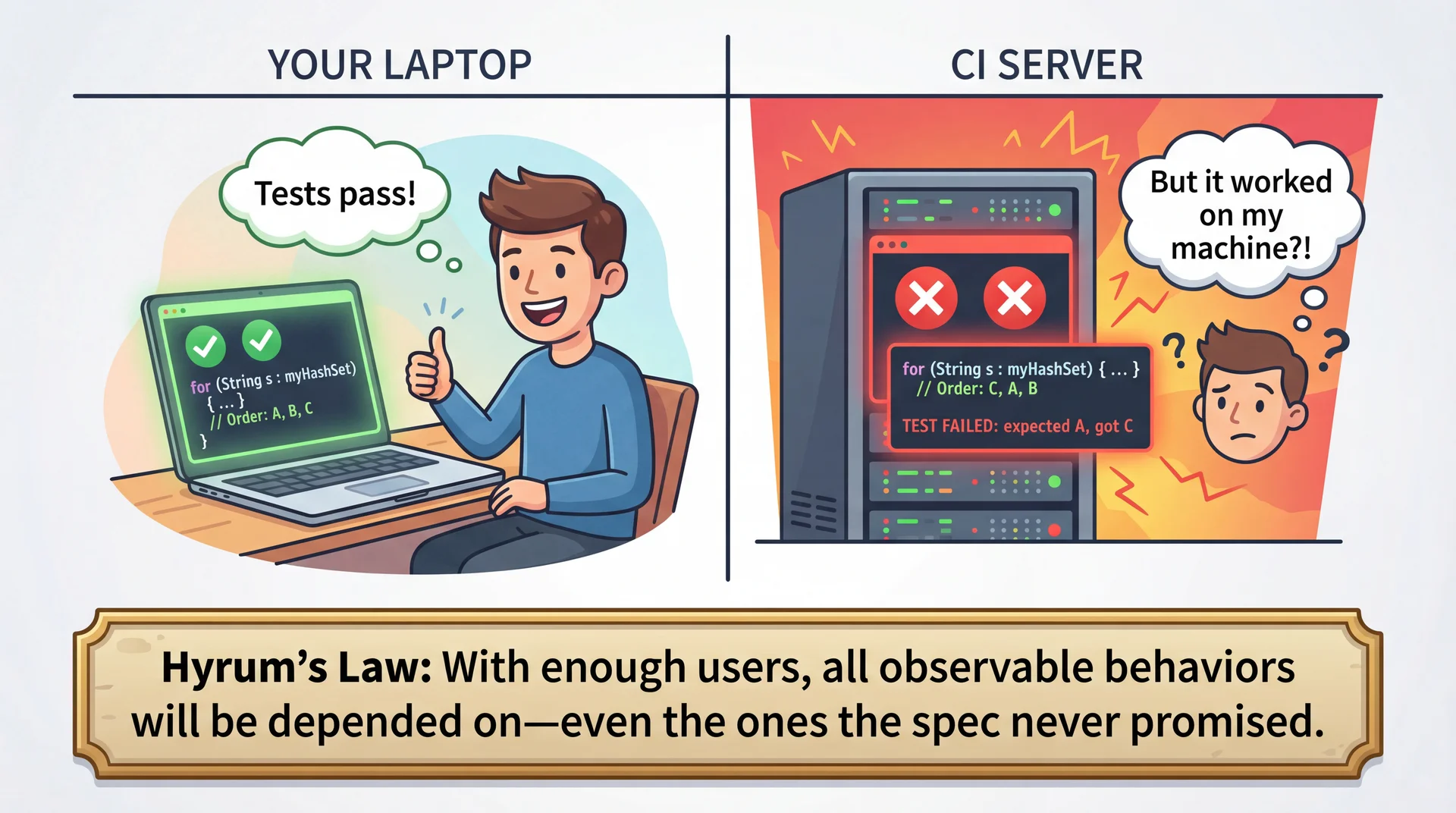

Silence in a Spec Means Undefined Behavior

❌ Underspecified:

/**

* Returns an iterator over

* the elements in this set.

* @return an Iterator over the

* elements in this set

*/

public Iterator<E> iterator()

Client might assume insertion order...

✓ Properly specified:

/**

* Returns an iterator over

* the elements in this set.

* The elements are returned in

* no particular order.

* @return an Iterator over the

* elements in this set

*/

public Iterator<E> iterator()

Assuming Unspecified Behavior Creates Flaky Tests

"Works on my machine" isn't a specification!

General Specs Don't Over-Constrain Implementations

A spec is general if it doesn't rule out implementations that would be correct.

Think of it as: "What GOOD implementations does this spec allow?"

- Does it describe WHAT the method does, or HOW?

- Could a faster algorithm satisfy it?

- Does it over-specify implementation details?

Operational Specs Reject Valid Implementations

❌ Too operational (not general):

/**

* Returns true if this set contains the specified element.

* Iterates through all elements using a for-each loop,

* comparing each element using equals().

*

* @param o the element to search for

* @return true if found, false otherwise

*/

boolean contains(Object o);

This spec requires O(n) linear search!

Describe Results, Not Algorithms

✓ The actual Set.contains() specification:

/**

* Returns true if this set contains the specified element.

* More formally, returns true if and only if this set contains

* an element e such that Objects.equals(o, e).

*

* @param o element whose presence in this set is to be tested

* @return true if this set contains the specified element

* @throws ClassCastException if the type of o is incompatible

* @throws NullPointerException if o is null and this set

* does not permit null elements

*/

boolean contains(Object o);

This permits: HashSet (O(1)), TreeSet (O(log n)), LinkedHashSet...

The Right Balance Depends on What Callers Need

Compare these two List methods:

General (contains):

/**

* Returns true if this list

* contains the specified element.

*/

boolean contains(Object o);

Any implementation OK

Specific (indexOf):

/**

* Returns the index of the first

* occurrence of the specified

* element, or -1 if not found.

*/

int indexOf(Object o);

Must return FIRST index

indexOf is more restrictive because callers need to know which occurrence.

The Most Dangerous Specs Are Misunderstood Specs

A spec is clear if readers understand it correctly.

The most dangerous specs are those where readers think they understand but don't.

- Too brief: Readers fill in gaps with assumptions

- Too long: Readers skim and miss important details

- Jargon-heavy: Readers guess at meaning

- Redundant: Readers wonder what's different about each statement

Redundancy Creates Confusion, Not Clarity

❌ Redundant (hurts clarity):

/**

* Closes this stream and releases any resources.

* This method closes the stream. After closing,

* the stream is closed and cannot be used.

* Closing releases resources held by the stream.

*/

void close() throws IOException;

"Close closes the closed stream" — we got it the first time!

Domain-Specific Terms Need Definitions

❌ Unclear (assumes domain knowledge):

/**

* Iterates over elements in natural order.

* @return an iterator in natural order

*/

Iterator<E> iterator();

✓ Clear (defines the term):

/**

* Iterates over elements in natural order.

* Natural order is defined by the elements' compareTo() method,

* with smaller elements appearing before larger ones.

* @return an iterator in ascending natural order

*/

Iterator<E> iterator();

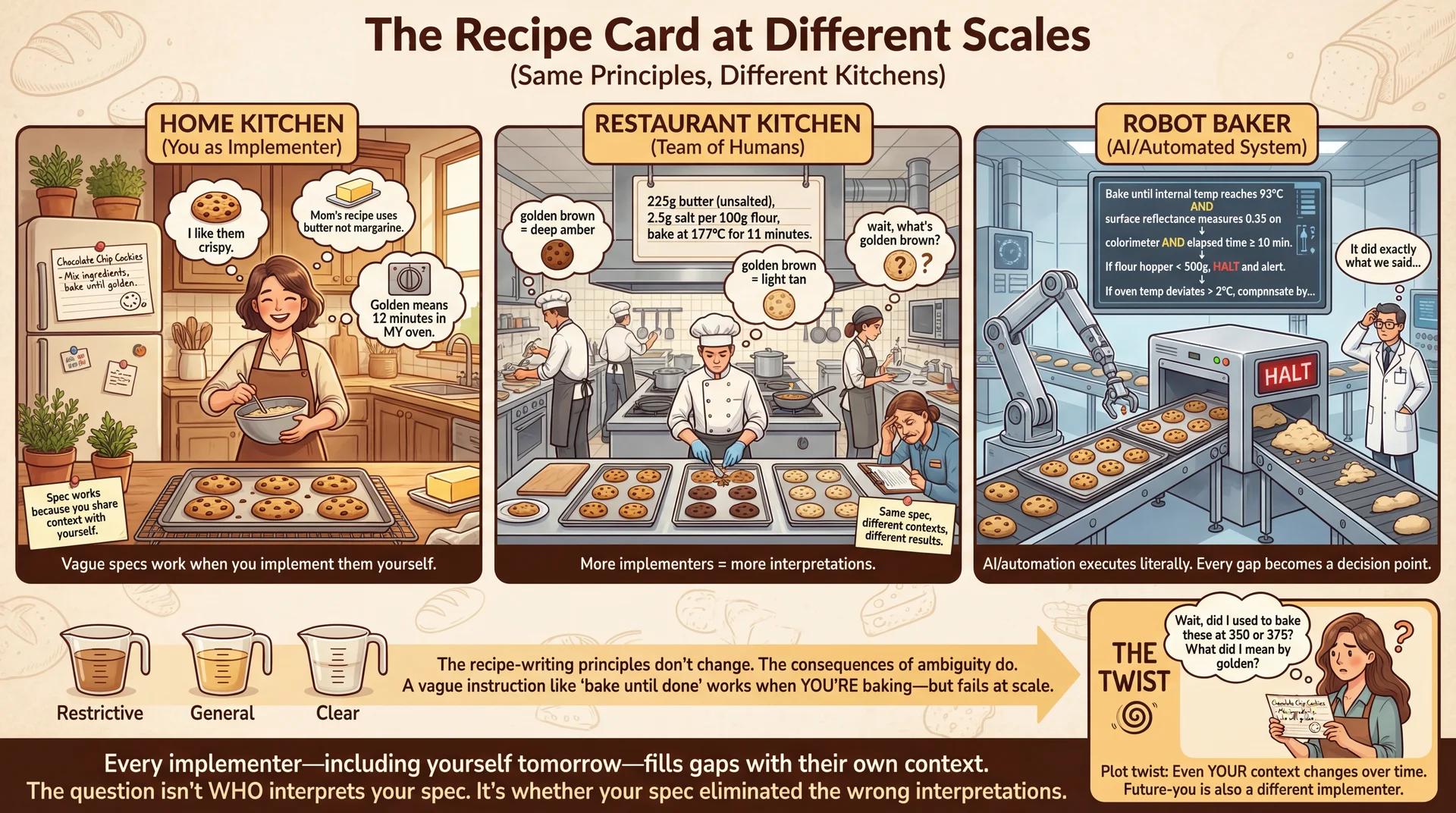

The Same Spec Principles Apply at Every Scale

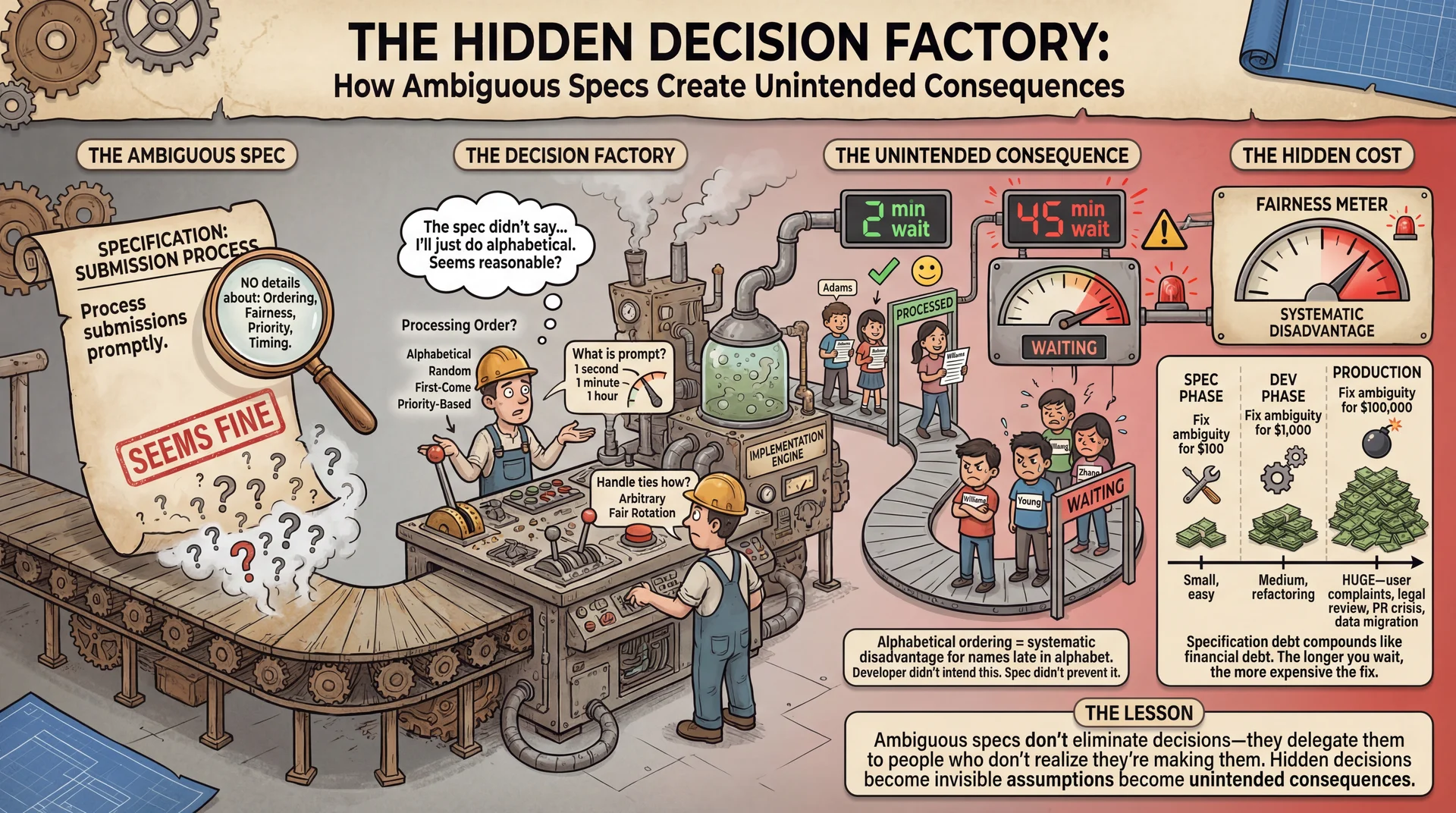

"Process" and "Handle" Are Not Specifications

Consider this IoT device manager API:

/**

* Handles the given device event.

*

* @param event the device event to handle

*/

public void handleEvent(DeviceEvent event)

What does "handle" actually mean? Every implementer fills the gap differently.

- Log it? Update device state? Notify other devices?

- What if the device is offline? Retry? Queue for later?

- Thread-safe? Can it be called concurrently?

Ambiguity Creates Specification Debt

Type Annotations Let Compilers Enforce Specs

![Concept: 'The Factory Quality Control Line' (Comments vs Type Annotations)

A detailed factory floor illustration in a clean industrial design style, showing two parallel assembly lines for 'Method Calls' being quality-checked before shipping to production.

LEFT LINE - 'HONOR SYSTEM QUALITY CONTROL' (Comment-Only Specs):

A conveyor belt carrying method calls (visualized as packages labeled with their arguments). A laminated sign hangs above: '📋 PLEASE CHECK: arr should not be null - Javadoc says so!' A tired human inspector sits on a stool, barely glancing at packages as they roll by. One package clearly labeled 'null' rolls past—the inspector is looking at their phone. Behind the inspection point: CHAOS. Packages explode on contact with the 'Production' area (labeled 'Runtime'), sparks fly, a NullPointerException alarm blares, developers in hard hats scramble with fire extinguishers. A whiteboard shows: 'Days since last null crash: 0̶ ̶3̶ ̶7̶ 0'. Annotation: 'Comments are suggestions. Humans skip reading them. Bugs ship to production.'

RIGHT LINE - 'AUTOMATED QUALITY GATE' (Type Annotations):

The same conveyor belt, but now it passes through an imposing automated scanner (glowing, precise, robotic). The scanner display shows: '@NonNull int[] arr — SCANNING...' Valid packages (with proper non-null arrays) get a green checkmark stamp and proceed smoothly to 'Production'. But the 'null' package hits an invisible force field—red lights flash, the scanner announces 'REJECTED: null violates @NonNull constraint', and the package is automatically diverted to a 'Fix Before Shipping' chute that loops back to the developer's desk. Beyond the gate: calm, orderly production floor. A whiteboard shows: 'Days since last null crash: 847'. Annotation: 'Type annotations are machine-enforced. Bugs caught before shipping.'

CENTER COMPARISON PANEL:

Split view showing the same code:

- Top: '// @param arr must not be null' + 'sum(null);' → Package makes it to production → 💥 RUNTIME CRASH

- Bottom: '@NonNull int[] arr' + 'sum(null);' → Package rejected at compile time → 🔧 Developer fixes it

DETAIL CALLOUTS:

- On the scanner: 'Powered by NullAway + JSpecify' with small logos

- Developer reaction left: 😰 'Why did this crash in production at 3am?!'

- Developer reaction right: 😊 'Caught it before I even ran the tests'

BOTTOM:

A timeline showing: 'Java 8 (2014): Type annotations added' with small portraits of the UW researchers. Caption: 'Moving specs from comments (that humans ignore) to types (that compilers enforce).'

Style: Industrial factory aesthetic with warm yellows/oranges on the chaotic left side, cool blues/greens on the orderly right side. Clean lines, clear labels, immediate visual contrast. Should feel like a safety training poster that makes a compelling case for type annotations. The factory metaphor works because it emphasizes: quality control BEFORE shipping is cheaper than recalls AFTER.](/img/lectures/web/l4-type-annotations.webp)

Type annotations let the compiler enforce specification invariants.

@NonNull Turns Documentation Into Enforcement

import org.jspecify.annotations.NonNull;

import org.jspecify.annotations.Nullable;

public int sum(@NonNull int[] arr) {

int sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

sum += arr[i];

}

return sum;

}

With @NonNull, the compiler enforces that arr is never null.

Note: Java has many competing @NonNull definitions. We use JSpecify.

@NullMarked Makes Non-Null the Default

Mark the whole package as "non-null by default":

// In package-info.java

@NullMarked

package edu.neu.cs3100.myproject;

import org.jspecify.annotations.NullMarked;

Now only mark exceptions with @Nullable:

// In a @NullMarked package:

public int sum(int[] arr) { ... } // arr assumed non-null

public String format(@Nullable String prefix, String value) { ... }

// prefix can be null, value cannot

Annotations Make Nullability Explicit at a Glance

// In a @NullMarked package

/**

* Formats a user's display name.

*

* @param firstName the user's first name

* @param middleName the user's middle name, or null if none

* @param lastName the user's last name

* @return formatted name (such as "John Q. Public")

*/

public String formatName(

String firstName, // non-null (default)

@Nullable String middleName, // explicitly nullable

String lastName // non-null (default)

) {

if (middleName == null) {

return firstName + " " + lastName;

}

return firstName + " " + middleName.charAt(0) + ". " + lastName;

}

Legacy Code Requires Gradual Annotation Adoption

Two approaches for existing codebases:

Approach A: @NullMarked (new code)

- Mark new packages @NullMarked

- Existing code left unannotated

- Gradually migrate package by package

Approach B: @NonNull everywhere (legacy)

- Don't use @NullMarked

- Add @NonNull as you verify each type

- Safer but more verbose

For this course: new projects use @NullMarked. You'll see this in starter code.

Unannotated Libraries Need Runtime Assertions

Even java.util isn't fully annotated! The checker can't know if library methods return null.

String name = "Alice";

List<String> names = List.of(name); // Checker: "might be null!"

System.out.println(names.size()); // Warning!

Use Objects.requireNonNull to assert your domain knowledge:

List<String> names = Objects.requireNonNull(List.of(name));

// Checker now knows names is non-null

Every Java Object Inherits Four Key Contracts

Every class extends java.lang.Object, which defines methods you should consider overriding:

toString()— human-readable representationequals(Object)— logical equalityhashCode()— hash value for collections

Plus the Comparable interface:

compareTo(T)— natural ordering

toString Should Be Concise But Informative

From the Java documentation:

"Returns a string that textually represents this object. The result should be a concise but informative representation that is easy for a person to read."

Default (useless):

DimmableLight@1a2b3c4d

Overridden (helpful):

DimmableLight(color=2700K,

brightness=100, on=true)

Good toString Saves Hours of Debugging

// From the IoT device hierarchy in L3

@Override

public String toString() {

return "DimmableLight(id=" + id + ", " +

"brightness=" + brightness + ", " +

"on=" + isOn() + ")";

}

Best practices:

- Include the class name

- Include fields that matter for understanding the object

- Format for readability (not just dump all fields)

When you System.out.println(deviceList), good toString() makes debugging easy.

What does this print (==)?

public class DimmableLight {

private String id;

private int brightness;

public DimmableLight(String id, int brightness) {

this.id = id;

this.brightness = brightness;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

DimmableLight light1 = new DimmableLight("living-room", 100);

DimmableLight light2 = new DimmableLight("living-room", 100);

System.out.println(light1 == light2);

}

}

A. true

B. false

C. I have no idea

What does this print (equals()) ?

public class DimmableLight {

private String id;

private int brightness;

public DimmableLight(String id, int brightness) {

this.id = id;

this.brightness = brightness;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

DimmableLight light1 = new DimmableLight("living-room", 100);

DimmableLight light2 = new DimmableLight("living-room", 100);

System.out.println(light1.equals(light2));

}

}

A. true

B. false

C. I have no idea

Where does equals() come from?

Object's implementation:

public boolean equals(Object obj) {

return (this == obj);

}

Since DimmableLight doesn't override equals(), it inherits this version—which just checks reference equality.

Overriding equals()

public class DimmableLight {

private String id;

private int brightness;

// ... constructor ...

@Override

public boolean equals(Object obj) {

if (this == obj) return true;

if (!(obj instanceof DimmableLight other)) return false;

return brightness == other.brightness

&& Objects.equals(id, other.id);

}

@Override

public int hashCode() {

return Objects.hash(id, brightness);

}

}

What's hashCode()? And why do we need it?

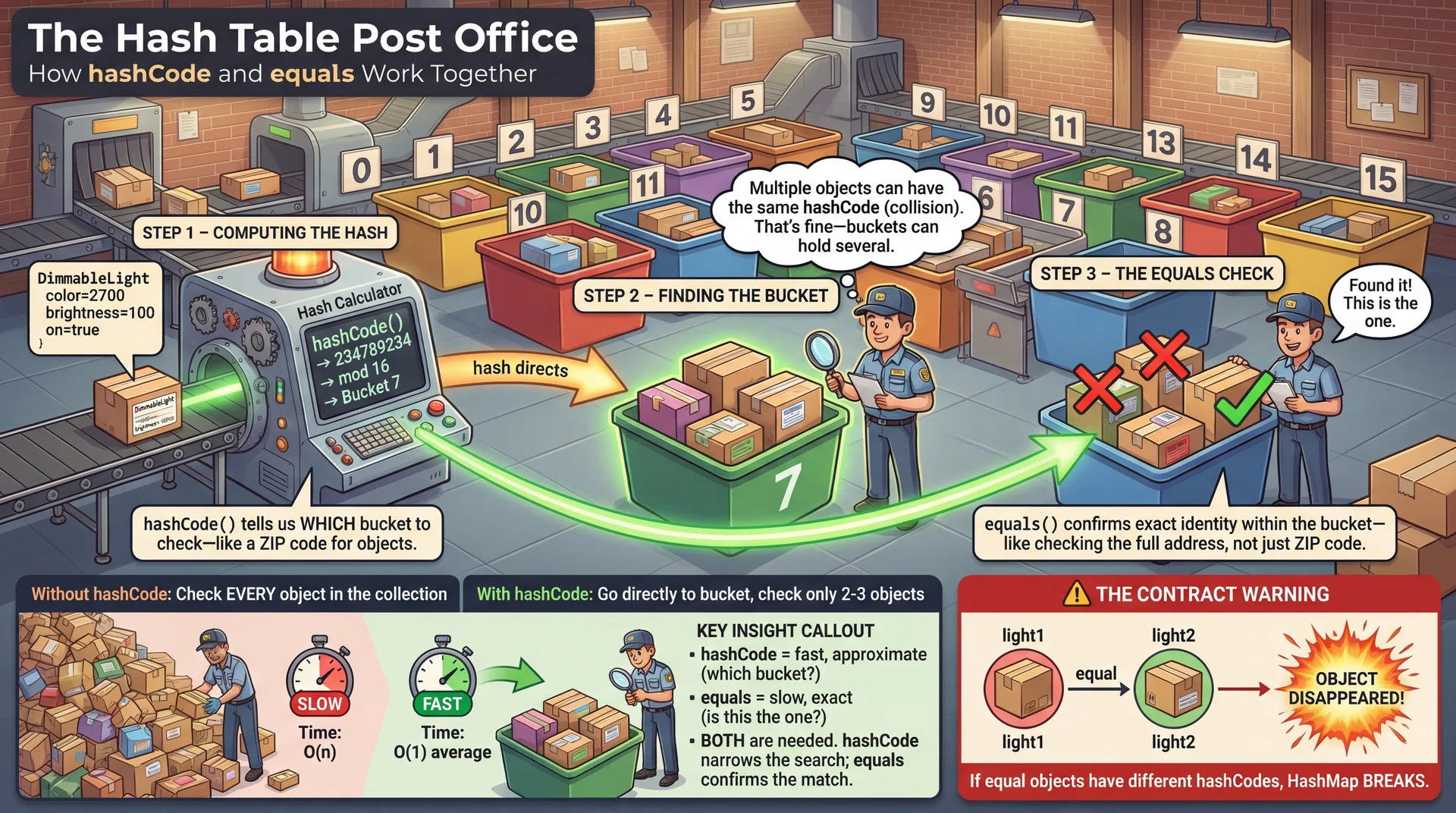

hashCode Enables O(1) Lookup in HashSets and HashMaps

Why override hashCode()?

Object's hashCode() returns a value based on the object's memory address.

Can two different objects have the same memory address? No.

// DimmableLight with equals() but NO hashCode() override

DimmableLight light1 = new DimmableLight("living-room", 100);

DimmableLight light2 = new DimmableLight("living-room", 100);

System.out.println(light1.equals(light2)); // true (we overrode equals)

Set<DimmableLight> lights = new HashSet<>();

lights.add(light1);

System.out.println(lights.contains(light2)); // false!

The problem: light1 and light2 are equal, but have different hash codes, so HashSet looks in the wrong bucket.

Equal Objects Must Have Equal hashCode() Values

The contract (simplified):

- Required: If

x.equals(y), thenx.hashCode() == y.hashCode() - Recommended: If

!x.equals(y), hash codes should differ - Required: Consistent within one execution

⚠️ If you override equals, you must override hashCode!

Use the Same Fields in hashCode as in equals

// For DimmableLight with fields: id, brightness

@Override

public int hashCode() {

int result = Objects.hashCode(id);

result = 31 * result + Integer.hashCode(brightness);

return result;

}

// Or simply:

@Override

public int hashCode() {

return Objects.hash(id, brightness);

}

Use the same fields as equals. See Effective Java Item 11 for details.

Sorting with the Comparable Interface

The Comparable Interface

public interface Comparable<T> {

/**

* Compares this object with the

* specified object for order.

*

* @return negative if this < o,

* zero if this == o,

* positive if this > o

*/

int compareTo(T o);

}

compareTo Defines How Objects Sort Naturally

For classes with a natural order, implement Comparable<T>:

/**

* A dimmable light. Lights are ordered by id, then by brightness.

*/

public class DimmableLight implements Comparable<DimmableLight> {

private String id;

private int brightness;

@Override

public int compareTo(DimmableLight other) {

int idCompare = this.id.compareTo(other.id);

if (idCompare != 0) {

return idCompare; // different ids

}

// same id, sort by brightness

return Integer.compare(this.brightness, other.brightness);

}

}

Returns: negative if this < other, zero if equal, positive if this > other

Summary: Specifications as Contracts

- Specifications enable modularity — you used HashMap without reading its 2000 lines

- Good specs balance three criteria:

- Restrictiveness — Map.get() specifies null for missing keys

- Generality — Set.contains() permits O(1) or O(log n) implementations

- Clarity — no redundancy, domain terms defined

- Type annotations make specs machine-checkable (@NullMarked, @Nullable)

- Object contracts (toString, equals, hashCode, compareTo) enable Collections to work

Critical rule: Override equals → MUST override hashCode (or HashSet breaks!)

Next Steps

- Assignment 1 due Thursday, January 15 at 11:59 PM

- Complete flashcard set 4 (Specifications & Contracts)

Optional readings:

- Effective Java, Items 10-14 (equals, hashCode, toString, Comparable)

- Liskov & Guttag, Chapter 9.2 (Specification theory)

- JSpecify Documentation (Nullness annotations standard)

Next time: Functional Programming and Readability