CS 3100: Program Design and Implementation II

Lecture 8: Changeability III — Principles for Inheritance

©2025 Jonathan Bell & Ellen Spertus, CC-BY-SA

Poll: Have you read any Effective Java?

A. Never heard of it

B. Not yet

C. I've found it online

D. I've skimmed parts

E. I've read 1 or 2 items

F. I've read many items

Learning Objectives

After this lecture, you will be able to:

- Apply the SOLID principles to evaluate and improve object-oriented designs

- Explain why composition is generally preferred over inheritance and identify cases where each is appropriate

- Describe rules for safely implementing inheritance in your own code

- Define the Decorator pattern and explain its relationship to design for change

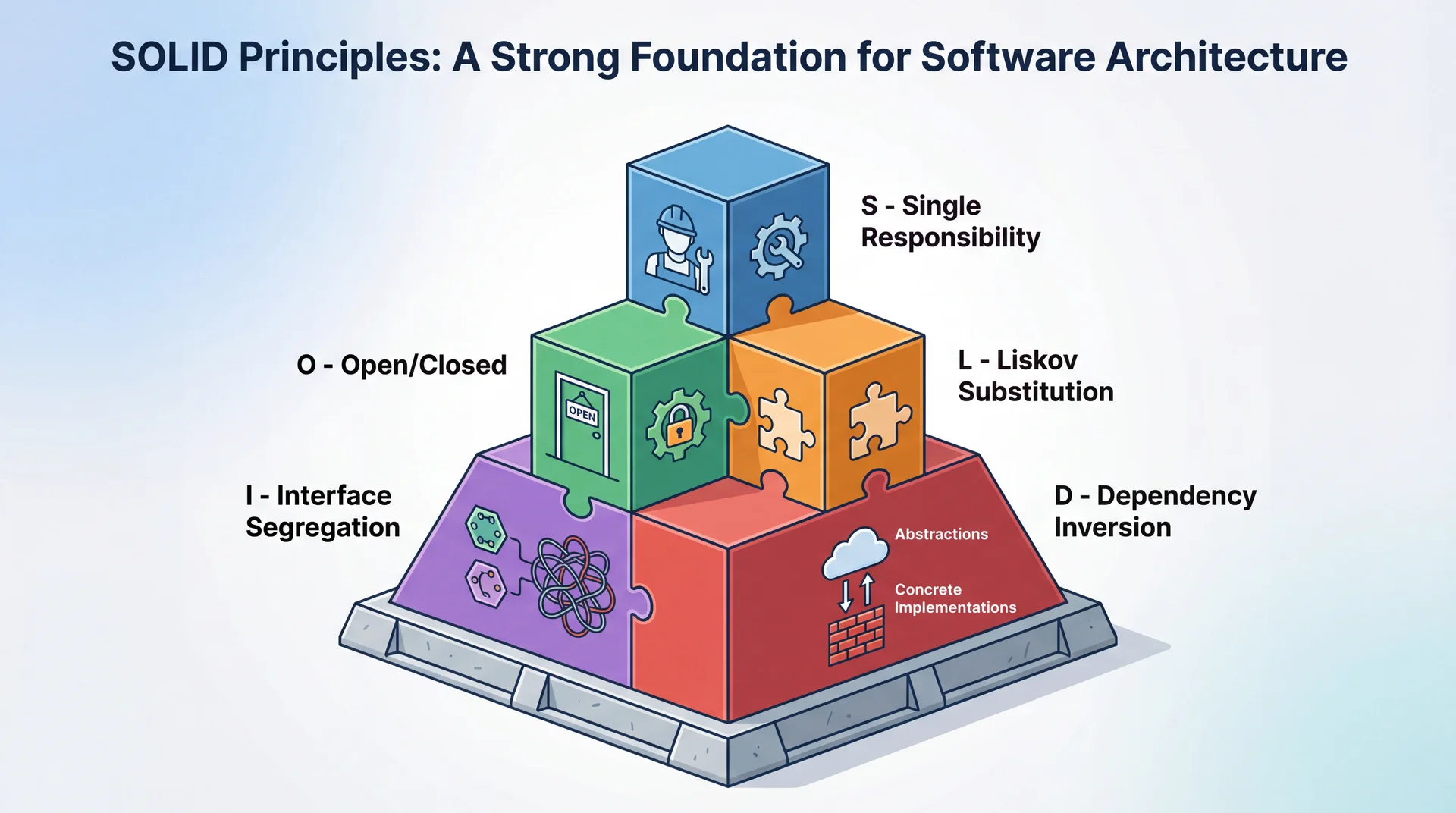

SOLID Principles Guide Decisions About Class Design

Classes With Multiple Responsibilities Are Hard to Change

Single Responsibility Principle: "A class should have only one reason to change."

This is cohesion applied to classes. A class with a single responsibility is easier to understand, test, and modify.

// Violates SRP - five reasons to change!

public class SubmissionService {

public void processSubmission(Submission submission) {

TestResult testResult = runTests(submission); // Testing logic

LintResult lintResult = lintSubmission(submission); // Linting logic

GradingResult grade = gradeSubmission(submission, testResult, lintResult); // Grading

saveSubmission(submission, grade); // Persistence logic

sendNotification(submission.student, grade); // Notification logic

}

}

SOLID: Single-Responsibility Principle

Delegation Separates Concerns Into Focused Classes

public class SubmissionProcessor {

private final TestRunner testRunner;

private final Linter linter;

private final Grader grader;

private final SubmissionRepository repository;

private final NotificationService notifier;

public void processSubmission(Submission submission) {

TestResult testResult = testRunner.run(submission);

LintResult lintResult = linter.analyze(submission);

GradingResult gradeResult = grader.grade(submission, testResult, lintResult);

repository.save(submission, gradeResult);

notifier.notify(submission.student, gradeResult);

}

}

✓ Each class has one job. Changes to linting don't touch testing or grading code.

SOLID: Single-Responsibility Principle

Can you create a subtype without modifying existing code?

public interface IoTDevice {

void identify();

boolean isAvailable();

}

public class Light implements IoTDevice {

// ... implementation ...

}

A. Yes, for both types

B. Only for IoTDevice

C. Only for Light

D. Not for either

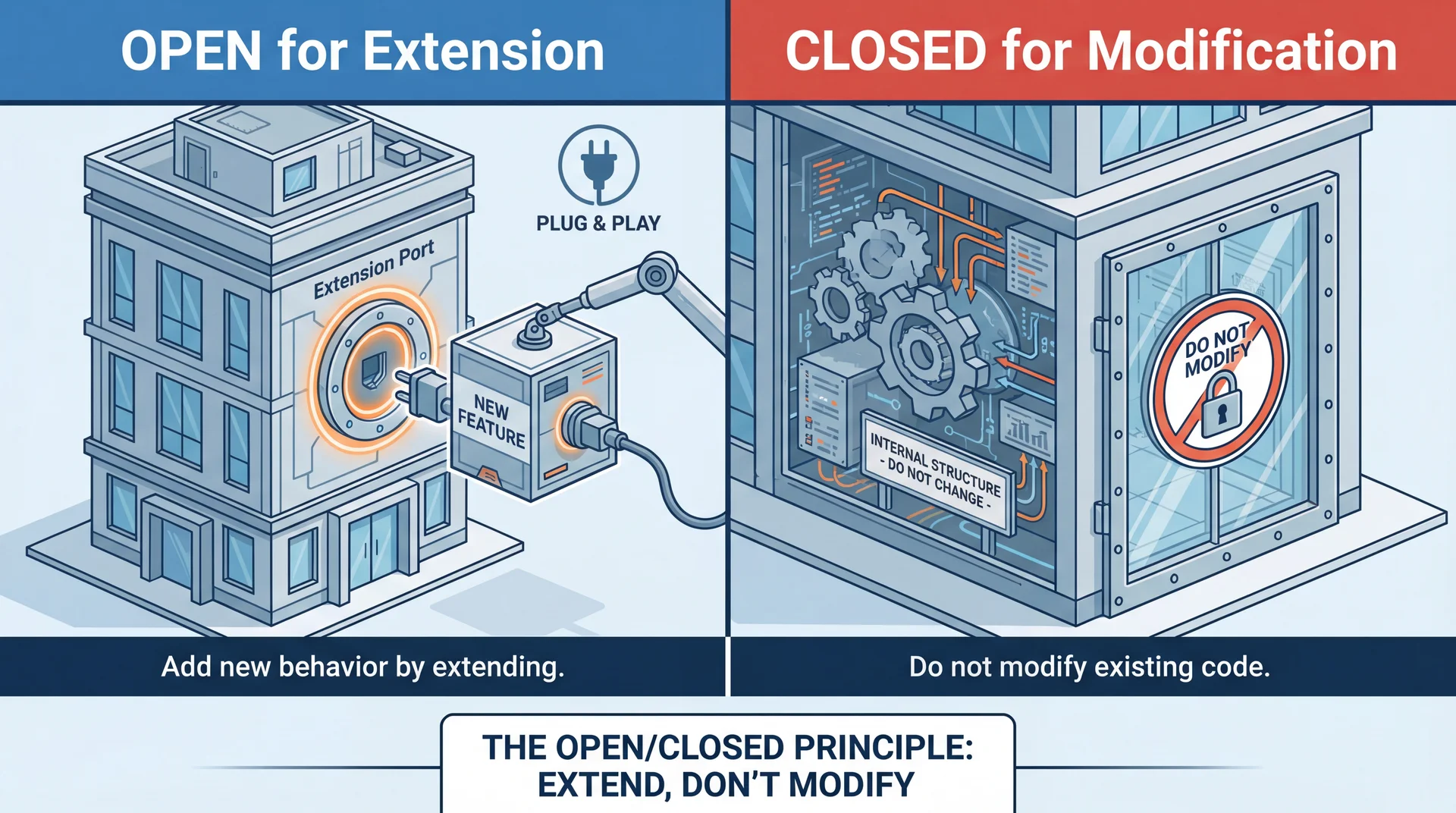

SOLID: Open-Closed Principle

Good Modules Can Be Extended Without Being Modified

Open/Closed Principle: "Software entities should be open for extension but closed for modification."

SOLID: Open-Closed Principle

Interfaces Enable Extension Without Modification

// Existing interface - OPEN for extension, CLOSED for modification

public interface IoTDevice {

void identify();

boolean isAvailable();

}

// Existing implementation - works, don't touch it

public class Light implements IoTDevice {

// ... implementation ...

}

// OPEN for extension - add new device types freely!

public class SmartThermostat implements IoTDevice {

@Override

public void identify() { /* Flash display */ }

@Override

public boolean isAvailable() { return true; }

// New behavior specific to thermostats

public void setTemperature(int temp) { /* ... */ }

}

Adding SmartThermostat doesn't require changing IoTDevice or Light.

SOLID: Open-Closed Principle

Poll: Which can be subtypes of Mammal?

A. Bird

B. Fish

C. Person

D. Plant

E. Cat

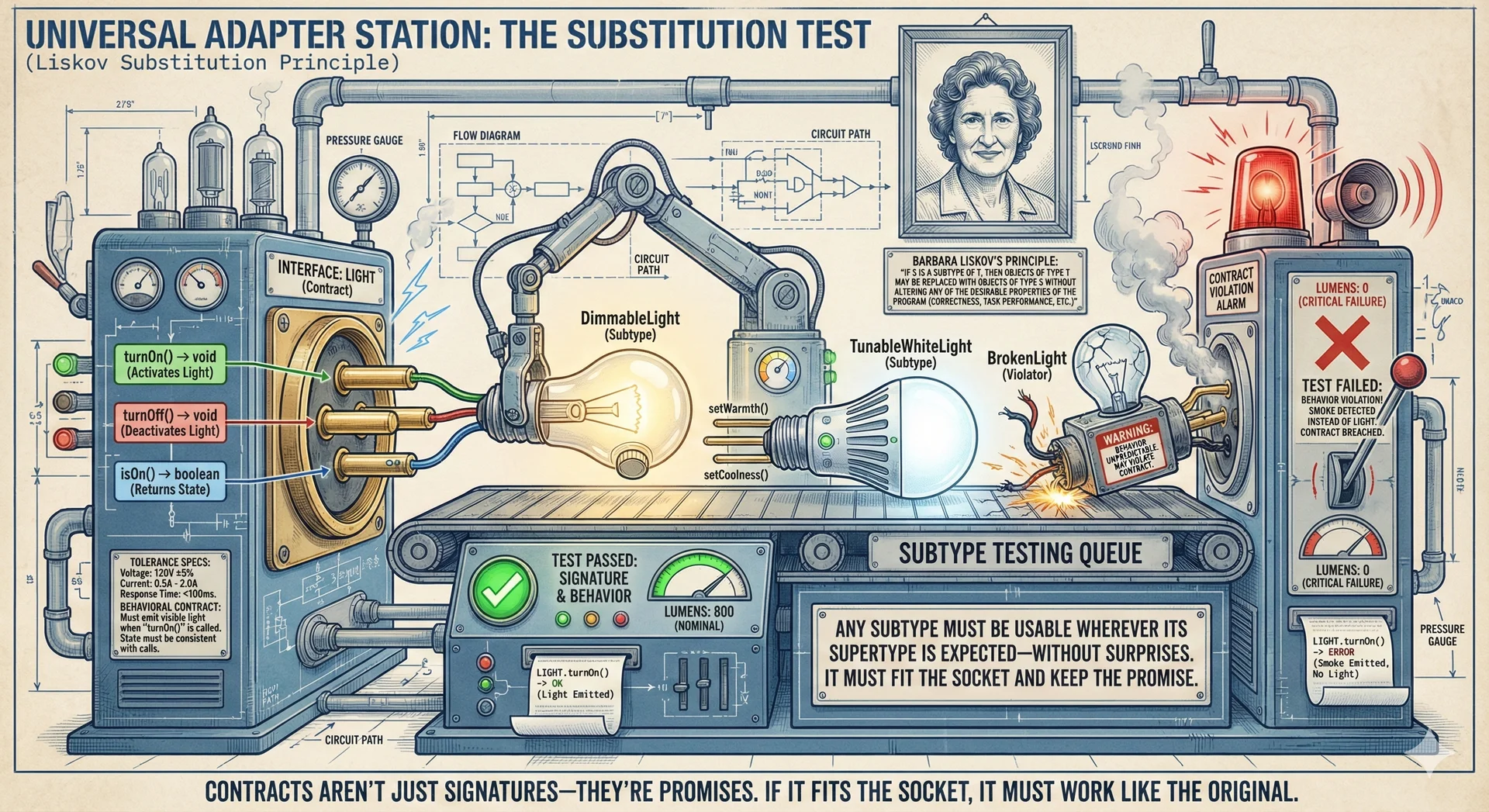

SOLID: Liskov Substitution Principle

Subclasses Must Be Substitutable for Their Parent Classes

Liskov Substitution Principle: Objects of a supertype should be replaceable with objects of its subtypes without breaking the application.

SOLID: Liskov Substitution Principle

Subclasses That Break Expectations Break All Calling Code

Good: LSP preserved

public class DimmableLight extends Light {

private int brightness = 100;

@Override

public void turnOn() {

// Honor contract by turning on light

super.turnOn();

// Can also add dimming capability

}

public void setBrightness(int b) {

this.brightness = b;

}

}

Bad: LSP violated

public class BrokenLight extends Light {

@Override

public void turnOn() {

// Does not honor contract!

throw new UnsupportedOperationException(

"This light can't be turned on!");

}

}

Code that calls light.turnOn() shouldn't need to check if it's a BrokenLight first.

SOLID: Liskov Substitution Principle

Poll: What type of interface(s) to prefer?

A: One large interface

public interface SmartDevice {

void turnOn();

void turnOff();

void setBrightness(int level);

void setColorTemperature(int temp);

void setFanSpeed(int speed);

}

B: Many small interfaces

public interface Switchable {

void turnOn();

void turnOff();

}

public interface Dimmable {

void setBrightness(int level);

}

public interface ColorAdjustable {

void setColorTemperature(int temp);

}

SOLID: Interface Segregation Principle

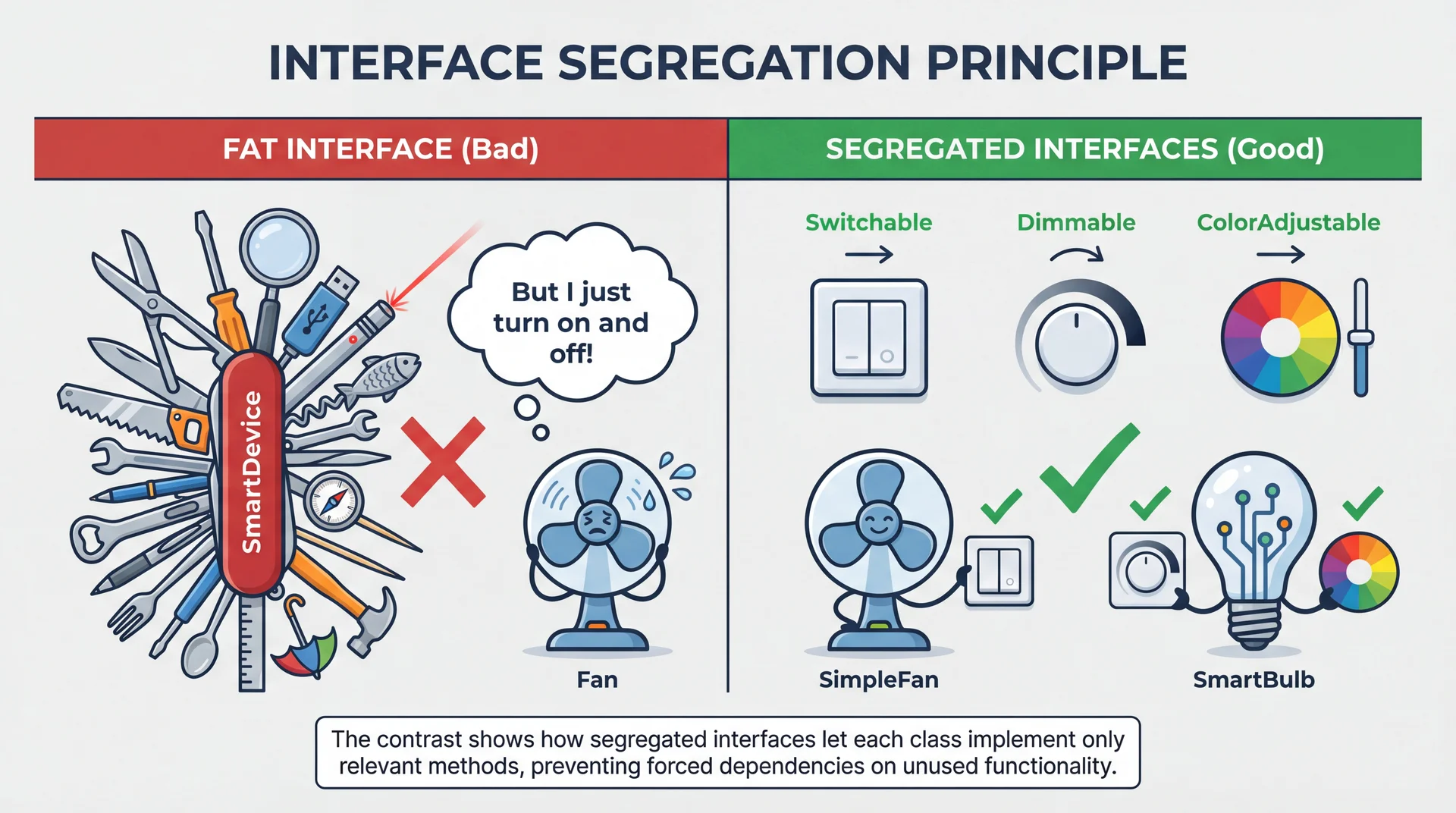

Large Interfaces Force Clients to Depend on Methods They Don't Use

Interface Segregation Principle: "Clients should not be forced to depend on interfaces they don't use."

SOLID: Interface Segregation Principle

Smaller Interfaces Reduce Unnecessary Dependencies

// Bad: Monolithic interface

public interface SmartDevice {

void turnOn();

void turnOff();

void setBrightness(int level); // Not all devices have this!

void setColorTemperature(int temp); // Or this!

void setFanSpeed(int speed); // Or this!

}

// Better: Segregated interfaces

public interface Switchable {

void turnOn();

void turnOff();

}

public interface Dimmable {

void setBrightness(int level);

}

public interface ColorAdjustable {

void setColorTemperature(int temp);

}

SOLID: Interface Segregation Principle

Classes Should Implement Only the Interfaces They Need

// Simple fan - just needs on/off

public class SimpleFan implements Switchable {

public void turnOn() { /* start motor */ }

public void turnOff() { /* stop motor */ }

// No need to implement dimming or color!

}

// Smart bulb - implements all capabilities

public class SmartBulb implements Switchable, Dimmable, ColorAdjustable {

public void turnOn() { /* ... */ }

public void turnOff() { /* ... */ }

public void setBrightness(int level) { /* ... */ }

public void setColorTemperature(int temp) { /* ... */ }

}

✓ Each class implements exactly the interfaces it needs—no more, no less.

SOLID: Interface Segregation Principle

Poll: Which dependency is better?

A: Dependency on concrete type

public class UserRepository {

private MySQL database;

public UserRepository(MySQL database) {

this.database = database;

}

}

B: Dependency on abstract type

public class UserRepository {

private Database database;

public UserRepository(Database database) {

this.database = database;

}

}

SOLID: Dependency Inversion Principle

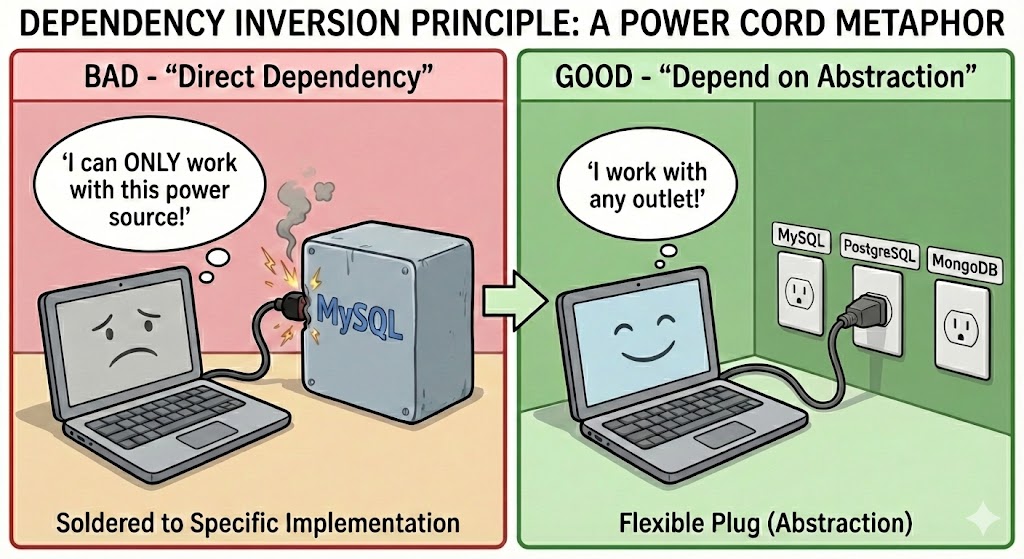

High-Level Modules Should Not Depend on Low-Level Details

Dependency Inversion Principle: "Depend on abstractions, not on concretions."

SOLID: Dependency Inversion Principle

Abstractions Allow Implementations to Be Swapped

Bad: Direct dependency

public class PawtograderSystem {

// Hardcoded to MySQL!

private MySQLDatabase database =

new MySQLDatabase();

public void saveSubmission(

Submission s) {

database.save(s);

}

}

Good: Depend on abstraction

public class PawtograderSystem {

private final Database database;

// Accepts any Database!

public PawtograderSystem(

Database database) {

this.database = database;

}

public void saveSubmission(

Submission s) {

database.save(s);

}

}

public interface Database {

void save(Submission submission);

}

SOLID: Dependency Inversion Principle

SOLID Principles Work Together to Enable Change

| Principle | Key Idea | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Single Responsibility | One reason to change | High cohesion |

| Open/Closed | Extend, don't modify | Safe evolution |

| Liskov Substitution | Subtypes honor contracts | Reliable polymorphism |

| Interface Segregation | Small, focused interfaces | Minimal dependencies |

| Dependency Inversion | Depend on abstractions | Loose coupling |

⚠ These are guidelines, not laws. Always consider trade-offs in your specific context.

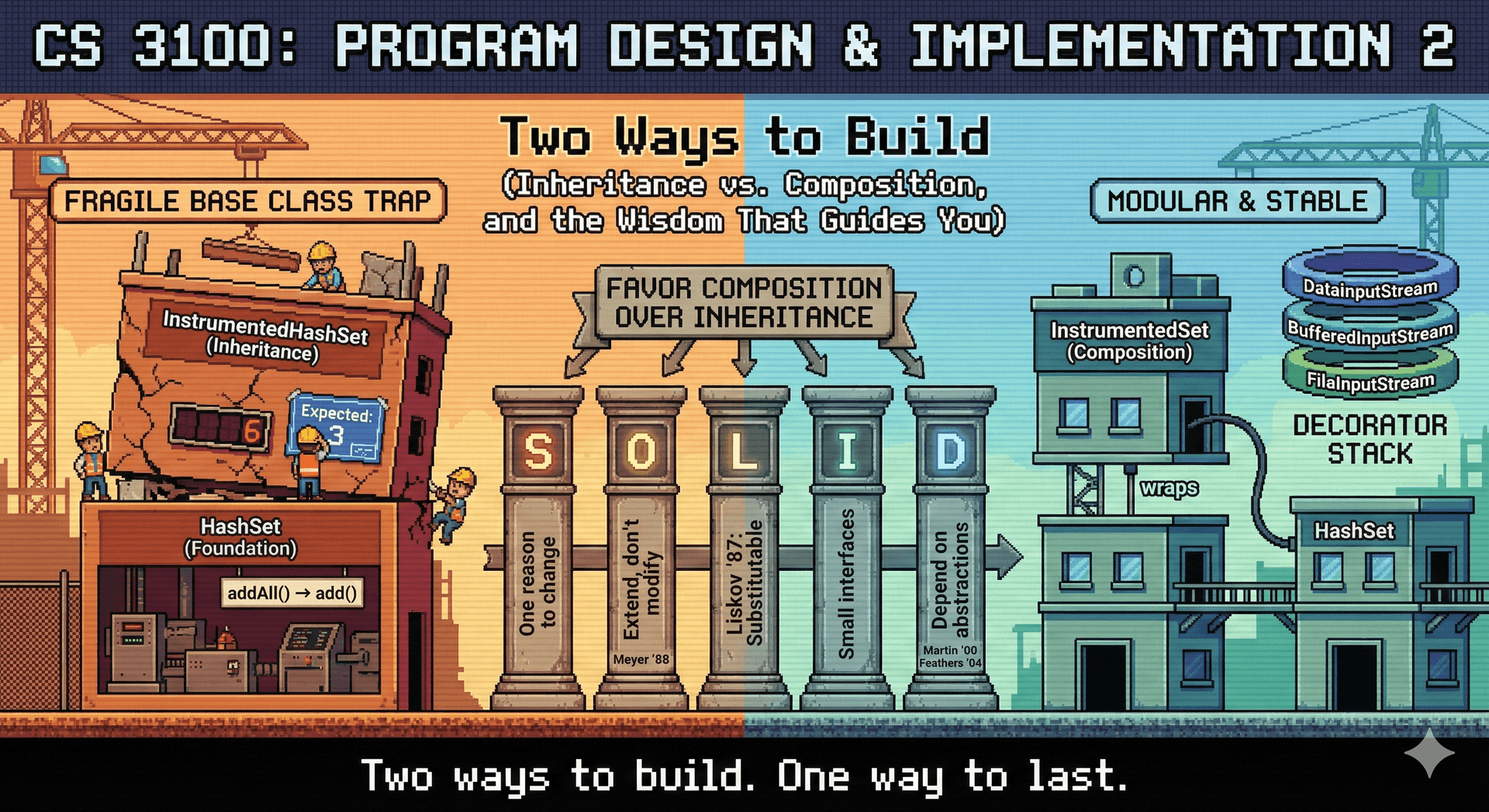

Inheritance Creates Tight Coupling That Composition Avoids

Effective Java Item 18: "Favor composition over inheritance"

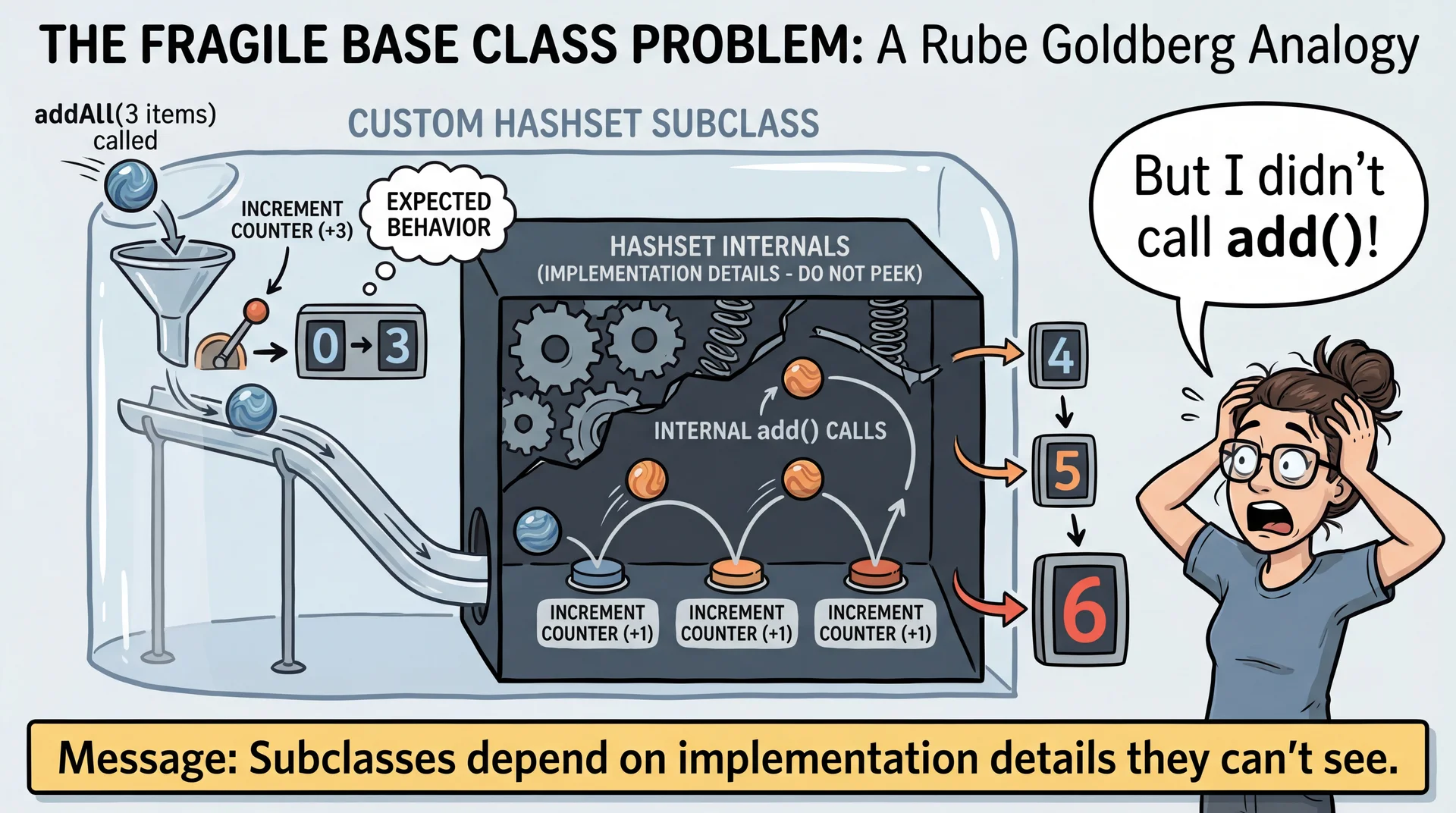

Subclasses Depend on Superclass Implementation Details

Imagine we want a Set that counts how many items are passed to add() and addAll():

public class InstrumentedHashSet<E> extends HashSet<E> {

private int addCount = 0;

@Override

public boolean add(E e) {

addCount++;

return super.add(e); // return true if added

}

@Override

public boolean addAll(Collection<? extends E> c) {

addCount += c.size();

return super.addAll(c);

}

public int getAddCount() { return addCount; }

}

What does getAddCount() return after s.addAll(Arrays.asList("A", "B", "C"))?

Hidden Implementation Details Cause Unexpected Behavior

InstrumentedHashSet<String> s = new InstrumentedHashSet<>();

s.addAll(Arrays.asList("A", "B", "C"));

System.out.println(s.getAddCount()); // Prints 6, not 3!

Composition Delegates Without Depending on Implementation

public class InstrumentedSet<E> implements Set<E> {

private final Set<E> s; // Composition: HAS-A Set

private int addCount = 0;

public InstrumentedSet(Set<E> s) {

this.s = s;

}

@Override

public boolean add(E e) {

addCount++;

return s.add(e); // Delegate to wrapped set

}

@Override

public boolean addAll(Collection<? extends E> c) {

addCount += c.size();

return s.addAll(c); // Delegate - don't care how it's implemented!

}

public int getAddCount() { return addCount; }

// Forward all other Set methods to s...

@Override public int size() { return s.size(); }

@Override public boolean isEmpty() { return s.isEmpty(); }

// ... etc ...

}

HashSet Class Hierarchy

Composition Keeps Method Calls Inside the Wrapped Object

Inheritance: count = 6 ❌

Composition: count = 3 ✓

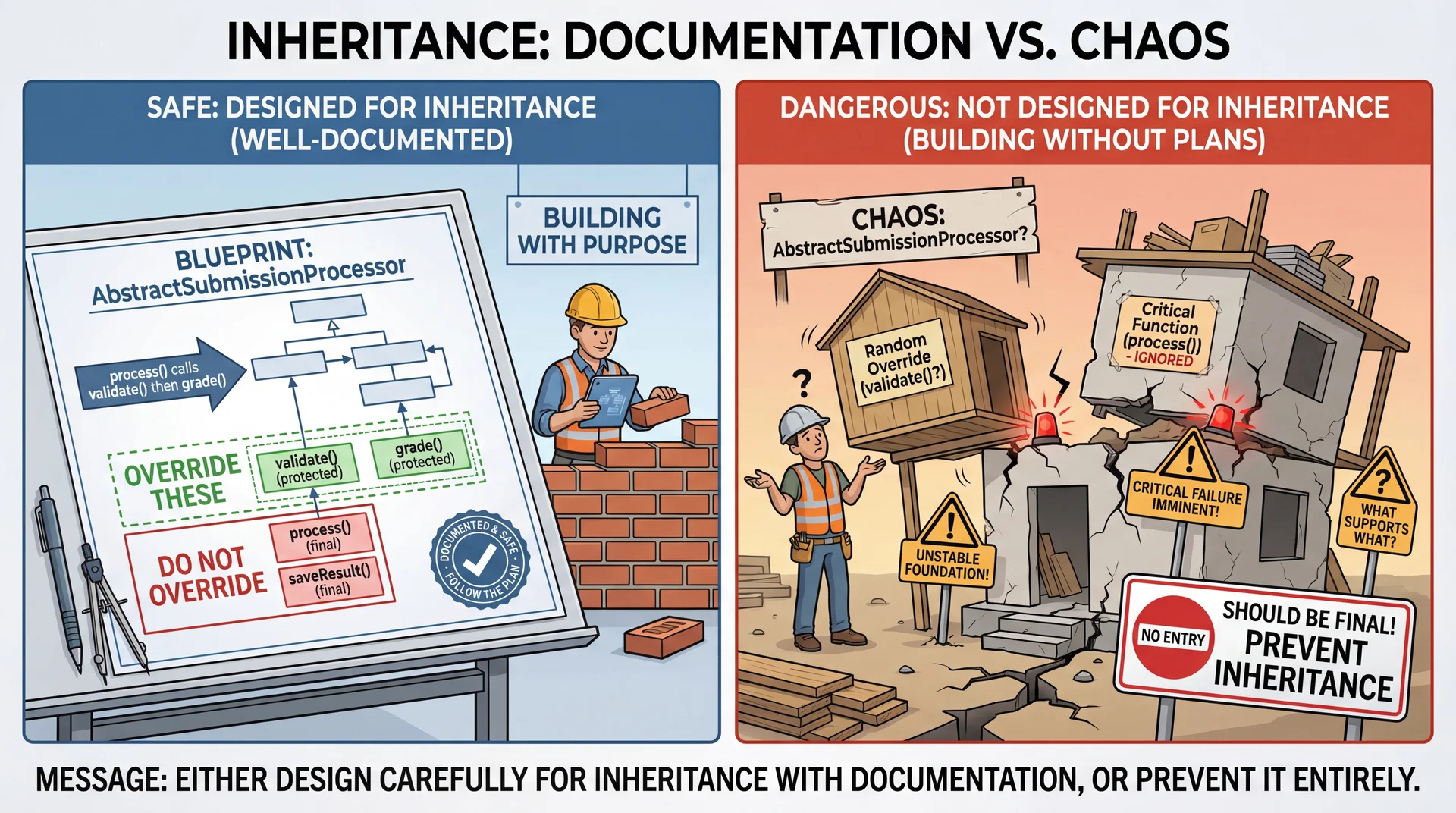

Inheritance Requires Explicit Design and Documentation

Effective Java Item 19: "Design and document for inheritance or else prohibit it"

Document Which Methods Call Which Other Methods

public abstract class AbstractSubmissionProcessor {

/**

* Processes a submission. This method calls {@link #validate(Submission)}

* followed by {@link #grade(Submission)} if validation succeeds.

*/

public final GradingResult process(Submission submission) {

if (validate(submission)) {

return grade(submission);

}

return GradingResult.invalid();

}

/**

* Validates a submission. Subclasses must override this method

* to provide language-specific validation.

*/

protected abstract boolean validate(Submission submission);

/**

* Grades a submission. Subclasses must override this method

* to provide language-specific grading.

*/

protected abstract GradingResult grade(Submission submission);

}

Most Classes Should Be Final By Default

// Prevent inheritance by making the class final

public final class SubmissionValidator {

// Cannot be extended - no surprises possible

public boolean validate(Submission submission) {

// Implementation details can change freely

// No subclass depends on them

}

}

Most classes should be either:

- Explicitly designed for inheritance with thorough documentation, OR

- Declared

finalto prevent inheritance entirely

Design Patterns

Popularized in a 1994 book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software

Strategy: swap algorithms at runtime via a common interface

Decorator: wrap objects to dynamically add behavior

Template Method: enable subclasses to customize algorithm steps

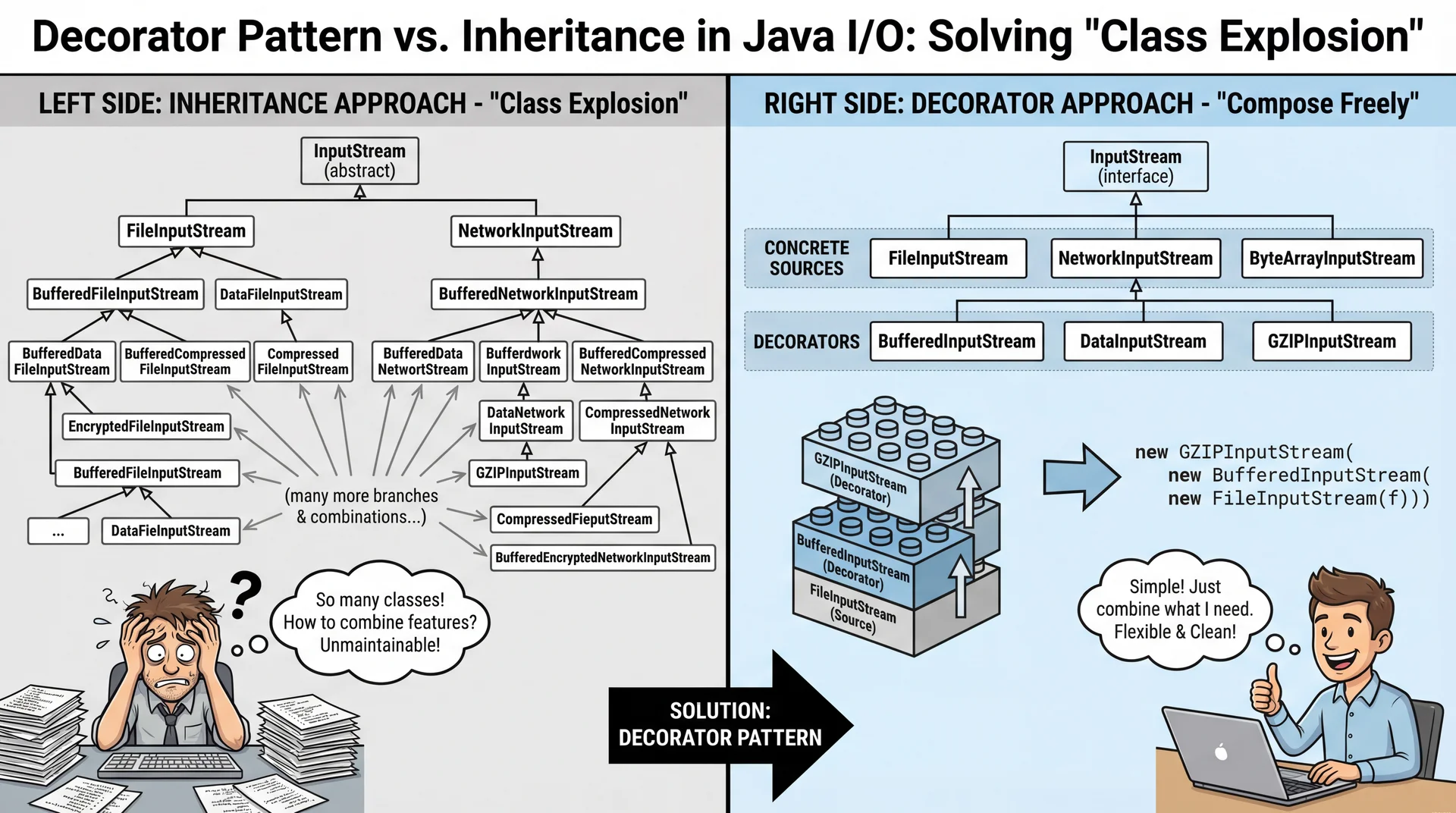

Decorators Add Behavior Through Composition, Not Inheritance

A structural design pattern that adds behavior to objects dynamically using composition.

Java InputStream

Java I/O Streams Stack Decorators for Flexible Combinations

Wrapping streams:

// Base: read bytes from file

InputStream file = new FileInputStream("data.txt");

// Decorator #1: add buffering

InputStream buf = new BufferedInputStream(file);

// Decorator #2: add primitive reading

DataInputStream data = new DataInputStream(buf);

int value = data.readInt();

Call delegation:

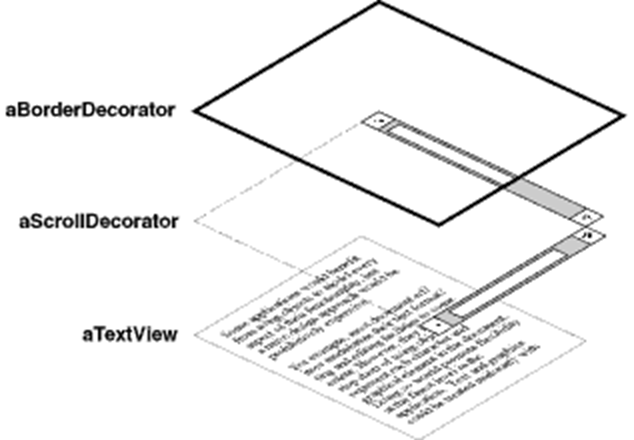

A Visual Decorator Example

Source: Design Patterns (1994) by Gamma et al., chapter 4

Decorators Avoid the Class Explosion Problem

Decorators Support Good Design Principles

- Single Responsibility Principle: Each decorator does one thing

- Open/Closed Principle: Add new decorators without modifying existing code

- Avoid class explosion: Compose instead of creating subclasses for every combination

Example combinations without new classes:

// Buffered file reading

new BufferedInputStream(new FileInputStream("data.txt"))

// Buffered, compressed network reading

new BufferedInputStream(new GZIPInputStream(new URL(url).openStream()))

// Data reading from bytes in memory

new DataInputStream(new ByteArrayInputStream(bytes))

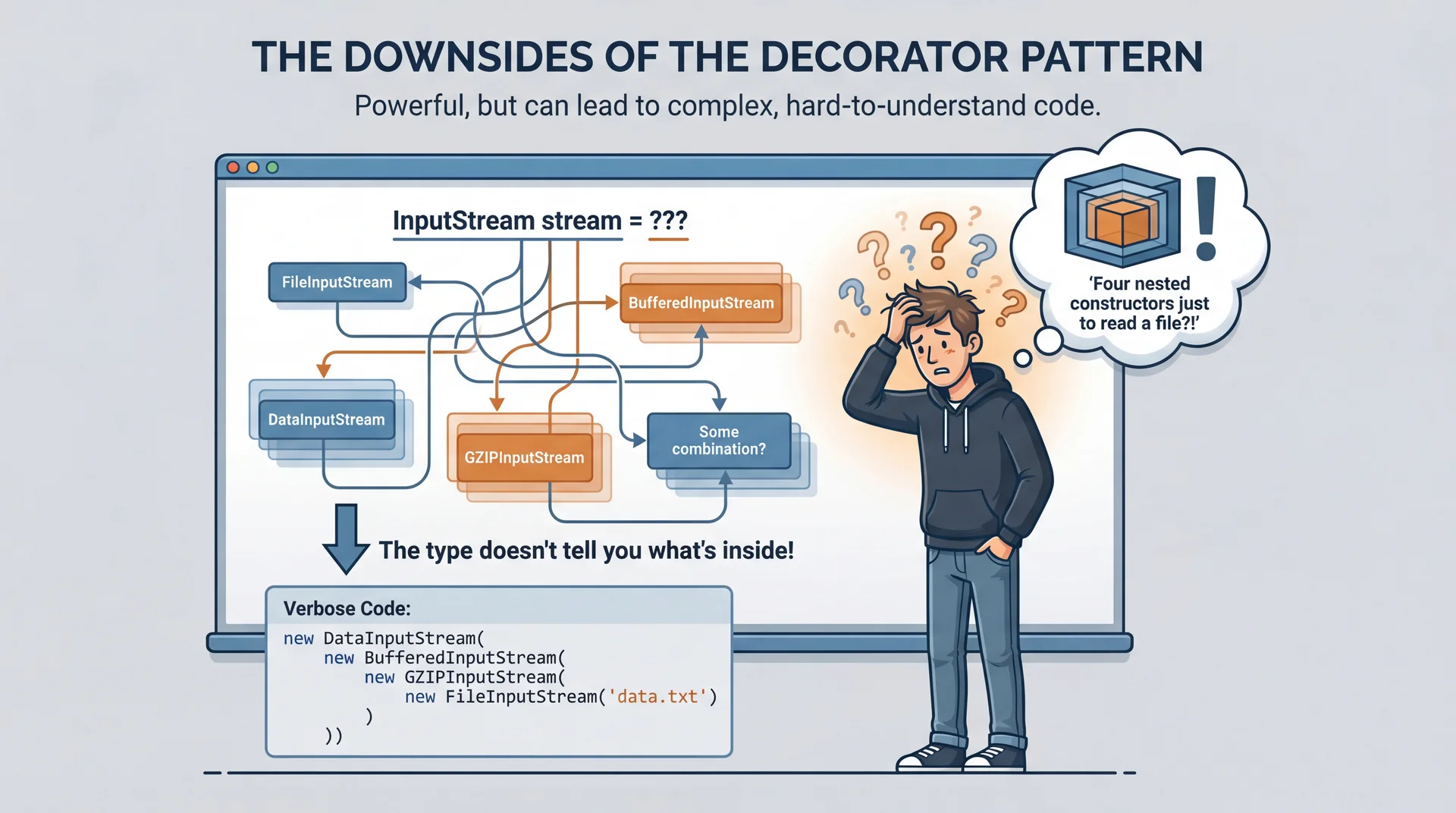

Decorators Trade Explicitness for Flexibility

- More verbose: Lots of wrapper instantiation

- Harder to understand: Can't tell capabilities from type alone

- Runtime composition: Structure hidden until execution

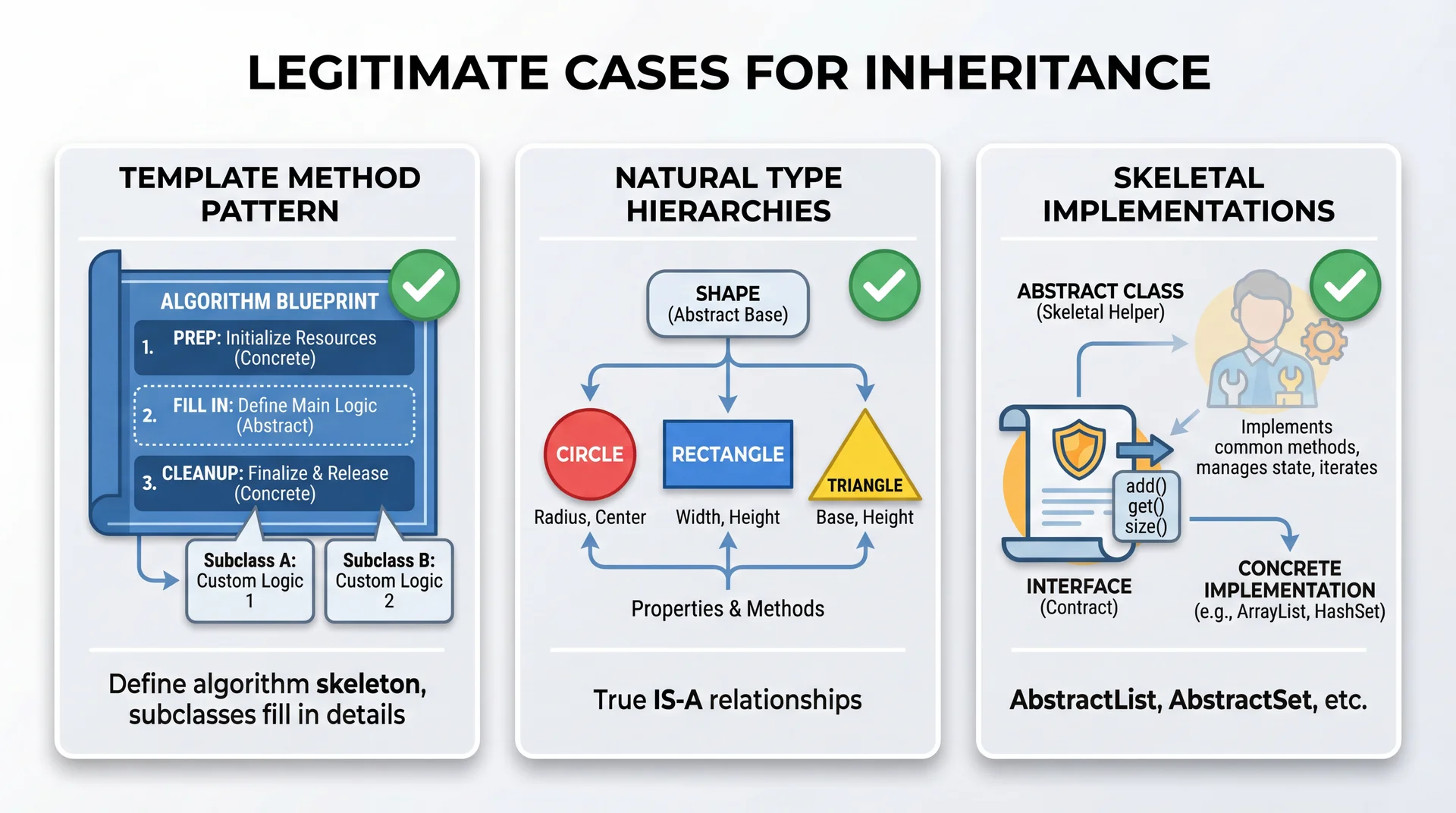

Inheritance Works Well for Specific Design Patterns

Template Methods Define Algorithm Skeletons That Subclasses Complete

Define the algorithm skeleton in the base class; let subclasses fill in the details.

public abstract class AbstractTestRunner {

// Template method - defines the algorithm structure

public final TestResult runTests(Submission submission) {

setUp();

try {

compileCode(submission);

List<TestCase> tests = loadTestCases();

TestResult result = new TestResult();

for (TestCase test : tests) {

beforeEach();

result.add(executeTest(test, submission));

afterEach();

}

return result;

} finally {

tearDown();

}

}

// Hooks with defaults // Abstract methods subclasses must implement

protected void setUp() {} protected abstract void compileCode(Submission s);

protected void tearDown() {} protected abstract List<TestCase> loadTestCases();

protected void beforeEach() {} protected abstract TestOutcome executeTest(

protected void afterEach() {} TestCase test, Submission s);

}

True "Is-A" Relationships Create Stable Hierarchies

public abstract class Shape {

protected double x, y; // Position

public abstract double area();

public abstract double perimeter();

public void moveTo(double x, double y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

}

public class Circle extends Shape {

private double radius;

@Override

public double area() {

return Math.PI * radius * radius;

}

@Override

public double perimeter() {

return 2 * Math.PI * radius;

}

}

✓ A Circle truly "is-a" Shape. The relationship is stable and meaningful.

Abstract Classes Can Provide Helpful Default Implementations

public interface Light {

void turnOn();

void turnOff();

boolean isOn();

}

// Skeletal implementation - does the boring work

public abstract class AbstractLight implements Light {

private boolean on = false;

@Override

public void turnOn() {

if (!on) { on = true; activateHardware(); }

}

@Override

public void turnOff() {

if (on) { on = false; deactivateHardware(); }

}

@Override

public boolean isOn() { return on; }

// Subclasses implement hardware-specific behavior

protected abstract void activateHardware();

protected abstract void deactivateHardware();

}

When to Use Inheritance

- There's a genuine "is-a" relationship fundamental to the domain

- You control both base and subclasses (or trust the base class designer)

- The base class is explicitly designed for inheritance with clear documentation

- You're implementing a well-established pattern like Template Method

- You need to share code between closely related classes

When to Avoid Inheritance

- You're trying to reuse code but there's no natural "is-a" relationship

- The base class wasn't designed for inheritance

- You want to modify behavior of existing classes (use Decorator)

- You want multiple inheritance of behavior (use interfaces with default methods)

- The hierarchy would be deep (more than 2-3 levels is often a smell)

Key Takeaways

- SOLID principles provide guidelines for changeable OO design

- Favor composition over inheritance to avoid the fragile base class problem

- Design for inheritance or prohibit it — document self-use or use

final - Decorator pattern adds behavior through composition, not inheritance

- Use inheritance for template methods, natural hierarchies, and skeletal implementations